It begins like a story told in a quiet room, one you lean in to hear, unsure where it will lead. A young man disappears into the storm of war. Time passes. Silence grows. And then, a letter arrives.

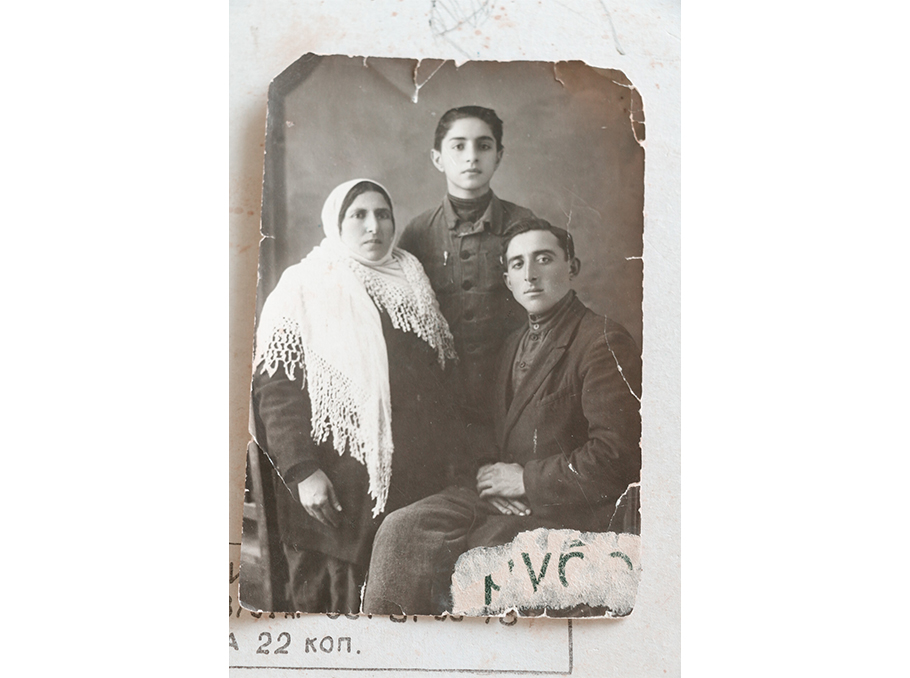

“They brought my grandmother the dreaded black envelope,” said Zhirayr, Aram’s son, a small ache rising in his throat. “She buried his childhood clothes. Held a funeral. And for years, she brought fresh flowers to an empty grave.”

Born in 1918 in the hillside town of Goris, Aram grew up in a family shaped by craft and quiet strength. He was the younger of two brothers–Levon, his senior by three years–and inherited from their father the delicate skill of watchmaking, a trade that would one day keep him alive. His father died early, leaving behind tools and timepieces, and a sense of precision that stayed with Aram long after childhood.

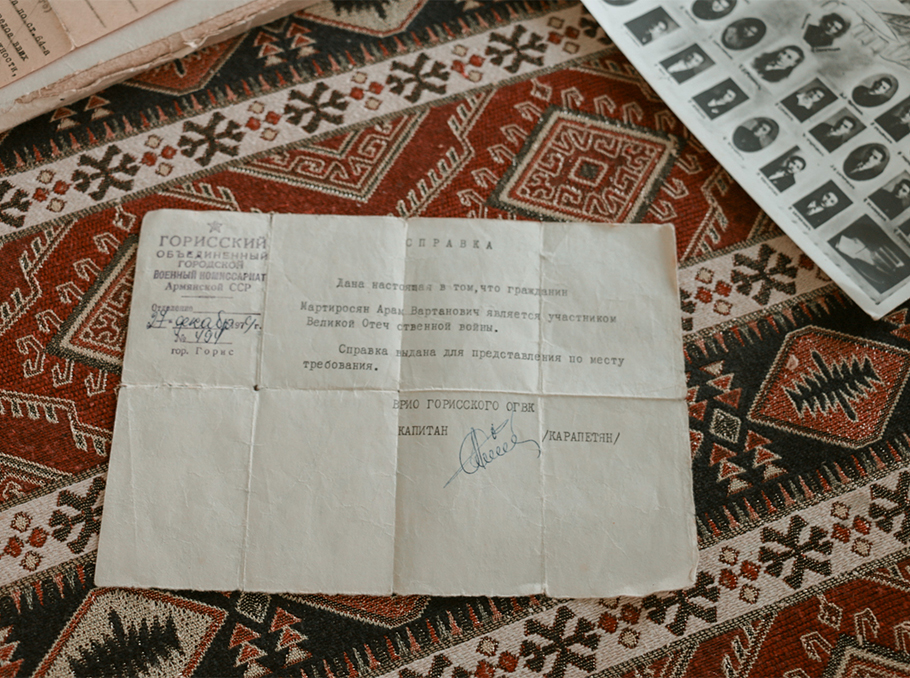

Later, he moved to Baku to study philology, drawn to language and literature with the same attentiveness he once gave to gears and springs. But history would interrupt that pursuit. In 1940, like many of his generation, Aram was drafted into the Soviet army–plunged into the heart of a war that would change the course of his life forever.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

Aram’s life took an unexpected turn as he found himself swept into the tumultuous currents of the Second World War. In 1940, he was drafted into the Belarus front, a pivotal moment that marked the beginning of his journey through the epicenter of global conflict. However, Belarus fell swiftly into German hands in 1941. Altogether, more than 2 million people were killed in Belarus during the three years of Nazi occupation. Martirosyan was among the imprisoned prisoners.

Belarusian prisoners were subjected to various forms of mistreatment and brutality by the German authorities. Many of them were conscripted into forced labor, used for tasks such as building infrastructure, working on farms, and supporting the German war effort. The conditions under which they were forced to work were often harsh, and many died due to exhaustion, malnutrition, and abuse.

It was during those grim, soul-breaking days in captivity that Aram Martirosyan met Alik, a fellow prisoner who would become his closest companion and, in many ways, a brother. Over time, as the months crawled by, the two men shared more than just bread and stories; they shared an unspoken vow to survive. One year into their imprisonment, amid the cold routines of suffering, they began to notice a pattern-the rhythmic flow of ammunition trains cutting through the forest near the camp in Ukraine. The trains came and went, always in a rush, always carrying something heavy toward the front lines. But occasionally, there were empty crates.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

From these fragments, a daring plan slowly took shape.

“They watched. Every morning, every evening… counting, observing,” said Zhirayr, Aram’s son, as he gently touched the worn photograph of his father, taken long before the war. He had retrieved it from a shelf where he kept Aram’s belongings, things too sacred to be left to dust. “It was risky, foolish maybe, but they had nothing to lose,” he added.

The plan was simple in form, but colossal in courage: they would climb into the empty crates being loaded onto outbound trains, letting fate carry them anywhere but there. They didn’t know where the tracks led-only that they had to try.

Eventually, the train slowed. The air was different now. As they emerged, stiff and silent, from the wooden box, Aram and Alik found themselves not in the East, but in the heart of France. The voices were unfamiliar, the signs unreadable, but they were free. Dazed by hunger and exhaustion, they wandered the streets until they came upon a glass-walled cafeteria. Desperate and unsure whether to step inside, they finally did.

By a stroke of incredible luck, or perhaps destiny, the café owner was Armenian. After hearing their story, he did not just offer them a meal; he became their bridge to salvation, helping them contact the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The organization, known for enforcing the Geneva Conventions and protecting prisoners of war, arranged for their medical check-ups and secured shelter for them. Soon after, Aram and Alik were placed with Armenian families, finally surrounded by kindness instead of barbed wire.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

Aram was placed with the Gyulbensaryan family–a quiet household of three: the husband, his warm-hearted wife, and their daughter, Shoushan. It was a modest home, but it radiated a gentleness Aram hadn’t felt in years. In this haven of calm, something unexpected began to blossom. Shoushan, with her quiet intelligence and kindness, brought light into Aram’s war-darkened world. What began as soft glances and thoughtful conversations grew into a tender affection–his first true experience of love, fragile and beautiful.

But even in freedom, sorrow had not loosened its grip.

Not long after settling in France, Alik fell gravely ill. The cold that had been gnawing at him in the camps returned as pneumonia, this time with no mercy. Aram stayed by his side as the days grew quieter. In one of their final conversations, Alik–his voice barely more than a whisper–asked one last thing of his friend: “When you make it back… find my mother. She lives at 10 Teryan Street… Yerevan.”

Aram promised, holding his friend’s hand as it slowly lost its warmth.

“He never forgot that promise,” Zhirayr added.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

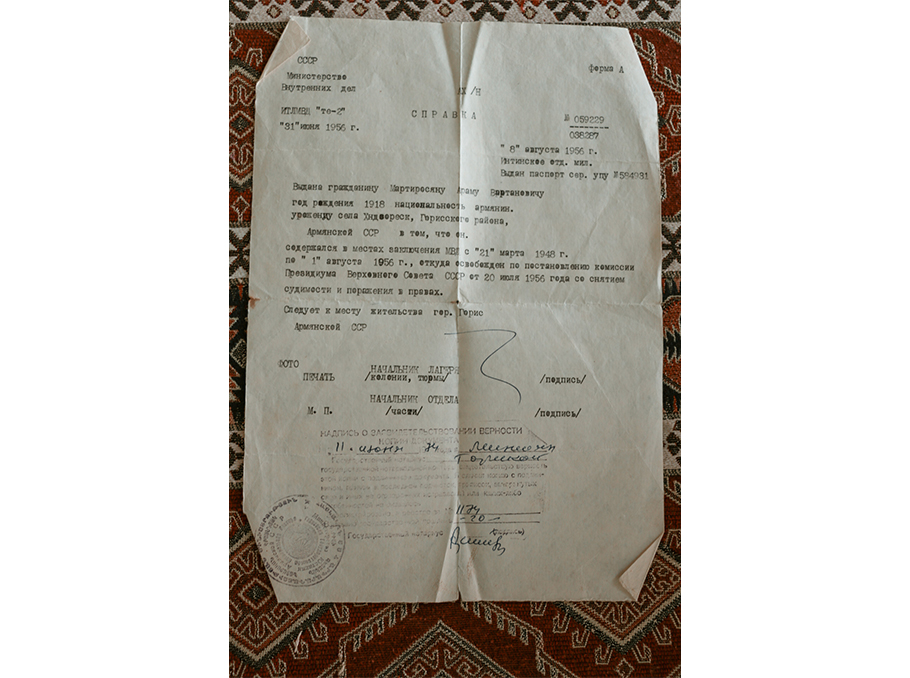

Under pressure from the Soviet regime, the Allies adopted policies of forced repatriation, resulting in an estimated 5 million Soviet citizens being returned to the USSR, willingly or not. There, they spent many more weeks and even months living in camps under an intense filtration regime run by SMERSH and the Soviet secret police (NKVD). Returnees were subjected to both medical and political inspections before being allowed to return to their homes.

After spending a year with the Gyulbensaryan family, Aram made the difficult decision to return to his homeland. Deep down, he knew this would wound those who had taken him in, especially Shoushan. Unable to face their sadness, he slipped away from Paris without a farewell, carrying the weight of a quiet goodbye that would never be spoken.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

Returning home felt like stepping into a dream. For years, Aram had been presumed dead. The thought of seeing his mother again filled him with both hope and dread. He first went to his aunt’s house, afraid that his sudden reappearance might break his mother’s heart. Always sharp in dress, Aram still carried himself with grace. When he arrived, his aunt stared at him blankly, whispering over and over, “Aram is dead.” But then, he removed his hat. Her voice faltered. Her eyes widened. Recognition flooded her face.

Unbeknownst to Aram, his mother was in the next room. The moment she saw him, there was no hesitation, no disbelief. She rushed toward him and wrapped her arms around his shoulders, crying out his name with the desperate tenderness of a mother reuniting with her child for the very first time.

“That’s my Aram …” she kept whispering, as if saying it aloud would anchor him in reality.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

And while recounting this, Zhirayr’s face softened. A small smile broke through, fragile but luminous, carrying the weight of all the tears he was holding back. It was as if, in that moment, he saw the boy his father once was, and perhaps even felt that boy still alive in himself.

Unlike in the 1920s, when the Soviet regime stripped millions of their citizenship, the authorities now wanted their people back. By 1941, SMERSH-short for “smert’ shpionam” or "death to spies", had established filtration camps across the Soviet Union. Returnees like Aram were thoroughly interrogated to confirm their identities and determine whether they were traitors or patriots.

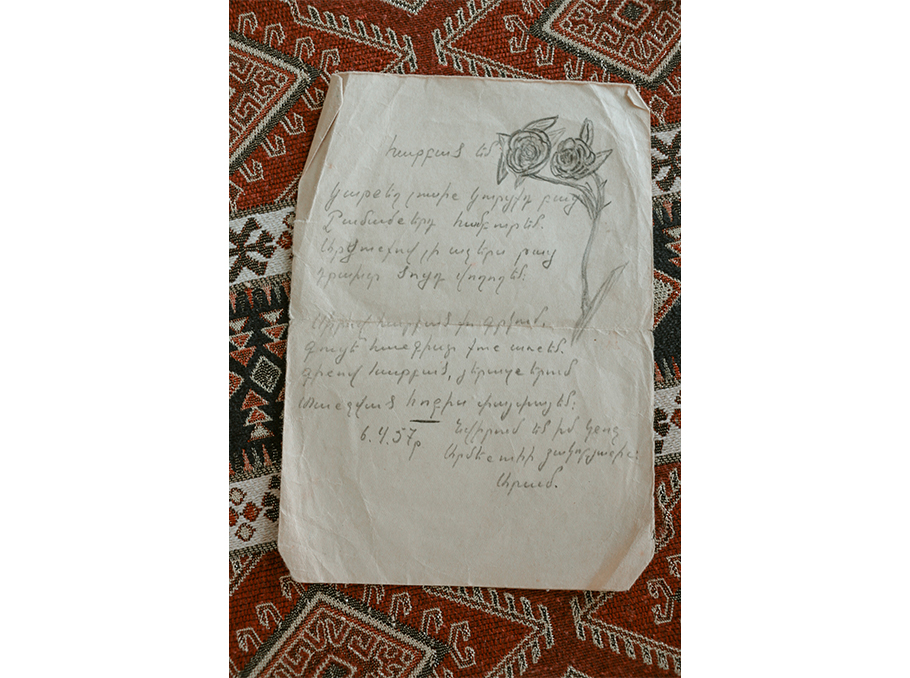

Back in Goris, Aram tried to rebuild a life. He worked as a watchmaker, the skill passed down from his father steadying his hands again. But joy was short-lived. Within months, his brother passed away, a cruel reminder of all that time had stolen. And history, relentless as ever, came knocking once more. Accused of treason, Aram was arrested and imprisoned. Yet even in his cell, stripped of freedom once again, he turned to poetry. In the quiet lines of verse, he poured the ache of injustice, the yearning for freedom, and the indomitable fire that had never left him.

“He was in the same cell as Charents, it was the same cell. My father thought so because there were Charents’ notes on the walls,” added Zhirayr, his voice gaining a colorful tone, as if the mention of Charents lit up something inside him.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

Aram was brought to court in Yerevan and subsequently faced trial in Armenia, which ultimately sentenced him to death by shooting.

“He lost consciousness the second he heard the decision,” said his son, and immediately Zhirayr’s eyes filled with the tears he had been trying to hold back, all the weight of the moment pressing against him.

In the prison where Aram was held, the guards had a chilling system, striking an iron bar to signal that an execution was about to take place. Yet Aram’s name was never called. Days passed in a blur of dread.

“I tend to believe someone just felt sorry for my father as he lost consciousness. They gave him 24 years in prison. They sent him to Vorkutalag, again to the strategic camp,” said Zhirayr.

And in that moment, his eyes held wavy emotions, as if, beyond the heaviness, they still hoped for at least something good.

Vorkutalag, one of the largest camps in the GULAG system, held over 73,000 prisoners at its peak in 1951. It imprisoned Soviet and foreign captives alike, political dissenters, prisoners of war, and ordinary people swept into the machinery of repression. They were forced into brutal labor: coal mines, timber work, construction in permafrost.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

Thanks to his intelligence and calm demeanor, Aram secured a position as the camp’s storekeeper, an assignment that offered a fraction more dignity in a world stripped of it. Every six months, prisoners were allowed to write a letter of self-defense. But hope often met silence.

Then came a turning point. After Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviet Union began its long, uneven process of de-Stalinization. The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet issued an amnesty that would release over 1.5 million prisoners-among them, men like Aram, who had waited years for a crack in the iron wall.

Aram Martirosyan was finally released from prison in 1956, tasting the sweetness of freedom after years of confinement.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

“He was 39 years old when fate led him to cross paths with my mother. He happened to meet my mother by chance. Both were already advanced in age, so their decision to marry felt like a conscious, deliberate choice," Zhirayr said, a gentle smile touching his lips.

Aram returned to his old trade, working tirelessly just to keep a roof over their heads. After marrying and having two children, he settled into what many would call a simple, normal life, something he had long been denied. Everything he never had, he tried to give to his sons, making his unfulfilled dreams come alive through them.

Though he left this world carrying many dreams still unfulfilled, he found peace in the end. Close to his passing, he received the long-awaited letter confirming his innocence. Aram Martirosyan died in 1982, in Goris.

“What kind of immoral world are we living in,” says Zhirayr, closing his eyes. His gaze, hiding a mix of sadness and happiness, pride and pain, seemed to gather all those tangled emotions. He seemed to want to put everything back in its place, because every time he tells this story, which is rare, all those feelings inside him swirl and blur.

Zhirayr himself is a painter and a member of the Union of Artists of Armenia and Artsakh, the Academy of Fine Arts of Russia, and the Society of Artists. He also serves as the director of Goris Gallery. He lives with his wife in his father’s old house and carries forward his father’s love for painting and writing.

Photo: Sophie Aghakhanyan

“I would like to write a book about my father. His life and memory mean so much to me, and I don’t want it to be lost. But I feel like this story is beyond my writing skills, so I’ve never dared to begin,” said Zhirayr, his voice trembling, as if touching that fragile theme might break something precious.

The story of his father is a deeply personal and vulnerable part of him, something he keeps close, protective and hesitant, yet longing for others to know.

“If I were to write that book, the title would be ‘The Traveler of the Forgotten Roads’. I feel like my father lived more than one life in his lifetime, spending them all searching for a genuine one, only to remain forever lost,” said Zhirayr, his voice heavy with emotion.

“He found Alik’s mother, Zhirayr added with a sudden shift in his voice, as if afraid he had almost forgotten to mention it – a promise to a brother kept. His eyes then grew calm once more.

Text and photos: Sophie Aghakhanyan

Comments

Dear visitors, You can place your opinion on the material using your Facebook account. Please, be polite and follow our simple rules: you are not allowed to make off - topic comments, place advertisements, use abusive and filthy language. The editorial staff reserves the right to moderate and delete comments in case of breach of the rules.