Mathematician Arthur Petrosian received his Master’s degree in Mathematics from Moscow State University in 1983 and a Ph.D. in Applied Mathematics from the Institute for Problems of Informatics & Automation, National Armenian Academy of Sciences, in 1989. He was a Visiting Scientist at the University of Belgrade, Yugoslavia (1991); an NIH supported Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (1992-93); and a Research Instructor at the Medical College of Ohio at Toledo (1993-94). He joined the faculty at Texas Tech University as an Assistant Professor in 1994, and was promoted to the Associate Professor level in 2000. In 2003, he joined the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) as a Scientific Review Officer. Since 2005 he has held the position of the Chief, Office of Scientific Review, at the National Library of Medicine, NIH. Dr. Petrosian is the author of more than 70 scientific articles, three book chapters, and two edited volumes. His main contributions in the fields of biomedical engineering have been the development of mathematical algorithms for predicting onsets of epilepsy and early recognition of Alzheimer’s disease.

I was born in Yerevan in 1960, in the family of a mathematician and a doctor. My father was a well-known mathematician in Armenia at the time, who worked with Academician Sergey Mergelyan and others to cofound the Yerevan Institute of Mathematical Machines (known as the Mergelyan Institute) and the Computing Centre of the Armenian National Academy of Sciences. Many of my father’s colleagues and students were frequent guests at our flat on Komitas Street. Although I was constantly interacting with mathematicians in my early childhood, during my high school years I seemed to be more interested in geography and economics than in math. I strongly believed I was going to choose one of those professions – yet in the end, my genes overpowered my intentions. I entered into the class of Mechanics & Mathematics at Yerevan State University in 1977, and transferred to the same class at Moscow State University (MSU) in 1980. I completed my master’s degree in Math in 1983 (Cum Laude), and in the same year entered into PhD under the supervision of Professor Vladimir M.Tikhomirov.

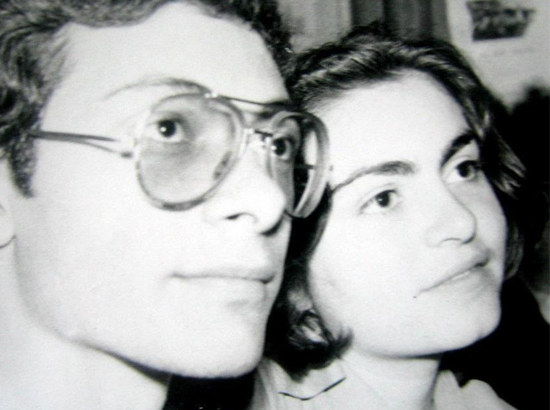

With friends at Moscow State University, 1982.

Photo from Arthur Petrosian’s personal archive.

Besides gaining a first class education in Math at the MSU, I benefited from being actively involved in the activities of Armenian students associations across Moscow’s educational institutions (the so-called “zemlyachestvo”). The friendships we made during those years have lasted a lifetime – we still organize meetings of the Armenian “zemlyachestvo” every two years, held at tourism spots either in Armenia or in Artsakh. Some 100-150 friends arrive from around the world to attend these gatherings, many with their grown up children.

During one of those meetings at the MSU in the early 80s Arthur happened to have met his future wife Narine.

With future wife in MSU, 1981.

Photo from Arthur Petrosian’s personal archive.

Like my father, after finishing studies at Moscow State University I decided to return to Armenia with my family. I already had a son who was 3 years old, and I wanted him to grow up in Armenia. I was admitted as a Research Associate to the Computing Centre of the Armenian Academy of Science, where I defended my PhD Thesis in 1989 (on Signal/Image Compression Theory and Applications). In 1990, we received a grant from the Biophysics Institute, USSR Academy of Sciences, to develop signal/image processing applications for biomedicine. A group of scientists at the Computing Centre began working under my supervision to create a comprehensive software package involving sophisticated techniques for statistical analyses and pattern recognition in biomedical signals. However, we were not able to complete our work. During the collapse of the Soviet Union 1991, we received notices from our management indicating that, in a matter of weeks, they may run out of salaries for employees. Little did we know then that the real tough times, including a war in Karabakh, were just on the horizon.

When Arthur was forced to leave Armenia, he already had two sons – 6 and 2 years of age. He tells that fortunately, he owned an old Soviet car (Zhiguli), and he was able to pack it with their belongings and move his family to Europe. They ended up in Belgrade, but just a few months later the war broke out in Yugoslavia.

We ended up in Belgrade, where both my wife and I found post-doctoral positions at the University of Belgrade. We loved living in Serbia and Belgrade; our kids started to learn the language and began attending schools there. Unfortunately, a few months later the war broke out in Yugoslavia too. When it spread to Bosnia, it became clear that we would be uncomfortable staying there for much longer. This was also a time of uncertainty in Armenia, so we made a decision to move further to the West – to the United States.

I was fortunate to have found my first job in the US relatively easily. My English was not particularly good at the time, and I quickly realized it would be hard for me to find a University position in Math. So I spent several months, day in and day out, in the University of Michigan library, trying to find openings where I could use the skills and knowledge I had acquired in applied signal/image analysis. Fortunately this was the time when the internet was just being created – free access to library computers provided me with a treasure trove of information at my fingertips. I was blown away by the ability to tap into a vast knowledge base of science and technology, and to retrieve the necessary papers and information via networked computers in a matter of minutes. Among many things liked in the US, I was highly impressed by the existence of such a powerful “digital infrastructure”. It was undoubtedly one of the most significant achievements and advantages of the US’s scientific enterprise, which gave it an edge compared to other countries.

Eventually I found a post-doctoral position in the Department of Radiology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (one of the best medical schools in US), to develop mathematical algorithms and software for detecting early breast cancer on digitized mammograms.

Skiing at Mont Tremblan, Canada.

Photo from Arthur Petrosian’s personal archive.

For about a year, I also worked part-time in the Department of Neurology at the Medical College of Ohio, helping neurologists there adopt non-linear dynamics methods for analyzing human brain waves (EEGs). In 1994, I was hired to continue this work as an Assistant Professor at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. This was an ideal opportunity for me to further develop my academic career in the multidisciplinary environment that Texas Tech had to offer.

Using his experience in biomedical engineering and signal/image processing Arthur was able to develop several active neurophysiology research programs there, particularly in the area of epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease. Arthur received major funding from the US Department of Health and Human Services, and from the Alzheimer’s Association to conduct studies on early detection of this disease.

I was also active in promoting and organizing several scientific meetings of international scope that were held at Texas Tech during those years. We cooperated in the field of wavelet theory and applications with some of my former colleagues at the Armenian National Academy of Science, which resulted in obtaining a grant from the US Civilian Research and Development Foundation (CRDF) to promote joint research on the topic. In 2001 I edited a book “Wavelets in Signal and Image Analysis: Form Theory to Practice” with 17 contributing authors, published by the Kluwer Academic Publishers. It provided a much-needed overview of current trends in the practical applications of wavelet theory in biomedicine and has been popular among graduate students and researchers working in biomedical signal and image analysis fields.

Some 10 years ago I was recruited by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) – the biggest institution in the world that funds biomedical research (NIH’s current budget is close to $30bln. annually). As with any other business area, the funding process for biomedical research in the US is organized in a competitive peer review manner. Researchers working at Universities and companies apply for funding to the NIH with proposals, which are then reviewed by independent panels of experts to select the most meritorious ones. The NIH then appropriates significant funds for supporting these scientists and their labs (an average NIH research grant budget is $350,000 per year).

At son’s graduation party at Stanford University.

Photo from Arthur Petrosian’s personal archive.

In 2005, Arthur became the Chief of the Office of Scientific Review at the National Library of Medicine (NLM is a part of the NIH).

NLM extramural programs support research in medical informatics fields, such as electronic health records, genomics/proteomics, computational biology, and public health informatics. My responsibilities at this current position include nominating experts to the NLM review committees, coordinating and supervising the work of these committees, and serving as expert and primary advisor to the NLM senior staff, and the NLM's Board of Regents, on issues and questions relating to review and evaluation of grant and contract proposals assigned to NLM.

For his work at NIH and NLM, Arthur has been honored with several awards, including the NIH and NLM Director’s Awards, and the Secretary’s Award, US Department of Health and Human Services.

While working at the NIH, I also helped several organizations in Armenia engage in promoting competitive peer review practices for funding local projects, including the National Foundation for Science and Advanced Technologies (NFSAT) and the State Committee on Science. I have also assisted the Armenian National Academy of Sciences to develop a centralized web portal – a database management/archival system for its research institutions and individual scholars, with an embedded functionality for providing dynamic/open peer review of their works (this project is still ongoing). Such a centralized database would be an invaluable first step towards creating a level “playing field” for scientists and researchers working inside Armenia. In addition, such a portal would have the potential to unite Armenian researchers both inside and outside Armenia without them having to travel and/or depend on the serendipity of chance social encounters. I presented the outline of this portal concept at the first ArmTech Congress held in San Francisco, California, in 2007.

With family at Zvartnots airport.

Photo from Arthur Petrosian’s personal archive.

Having followed closely the difficulties and a few recent successes Armenia has experienced in maintaining its scientific potential, Arthur says he is still optimistic about the future of Armenian science.

The good news is that Armenia has always been full of talents and creative scientific minds, and the new generation is not an exception. Empowered by the Internet and global access to educational sites, the next generation of Armenian scientists and researchers will undoubtedly rise to the same levels as their proud predecessors did during the Soviet times.

Arthur says that it is always unwise to make predictions about future; he does believe, however, that one day he’ll be able to make another comeback to Armenia.

I feel like the right time may be approaching for me to utilize the knowledge and skills I’ve gained during my 23-year career in the US to give back some of the debt I owe to the country of my origin. Life is still not easy in Armenia, I realize that. But there comes a time in everyone’s life, particularly if one’s kids have grown up and are self-sustainable (both my sons have now chosen careers in computer science in Silicon Valley – staying true to their grandfather’s genes), when one gets more pleasure from the spiritual aspects of his/her existence rather than from any material wants and needs. And when it comes to a spiritual connection, there is no other country on earth to which I can have a deeper connection with than Armenia.

In Sanahin, with MSU friends.

Photo from Arthur Petrosian’s personal archive.

I have visited Armenia multiple times over these 23 years (more than once a year on average), and have remained attached to my friends and family that live there. I know I will have no trouble adjusting whenever I make the move back. I also hope I’ll have more time to spend on my hobbies: playing chess, skiing, and helping to promote and re-instate the wine culture in Armenia.

Aram Araratyan