Since the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2022, there have been regular reports of rapprochement between Russia and Iran, starting with the delivery of drones and culminating in Tehran’s decision to join BRICS (the intergovernmental organization that also comprises Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia and the United Arab Emirates). From the Western perspective, the situation seems clear —two antagonists to the liberal international order are uniting. However, this simplifies complex geopolitical processes, particularly in the South Caucasus, which must be studied more thoroughly.

Cooperation and competition between Russia and Iran

Russia and Iran have a long and extensive history of bilateral cooperation. Currently, the most significant areas of collaboration are in the military-technical, energy, and economic sectors. Key milestones in the military-technical sphere include Russia’s delivery of S-300 air defense systems in 2016 and an accord on the supply of Su-35 fighter jets and Mi-28 helicopters. Following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, deliveries began flowing in the opposite direction, with Iran’s Shahed-136 drones being the best known. Cooperation in the energy sector includes agreements on Iran’s supply of gas turbines, Russia’s allocation of a $1.4 billion loan for constructing a thermal power plant in Iran, and agreements on swap gas supplies. A memorandum was signed for a $40 billion investment by Gazprom in Iran’s oil and gas sector. Despite declining trade volume at the end of 2023, Iran signed a free trade zone agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) in the economic sector. The ongoing integration of payment systems is also expected to boost trade and economic growth. Amid this cooperation, Moscow and Tehran plan to sign a partnership agreement covering all strategically important areas.

Such a picture may create the impression that Russian-Iranian relations are developing smoothly without any obstacles, from security to the economy. However, the marked achievements on the bilateral track have run into serious problems. For example, the agreement on S-300 systems was reached in 2007. Due to United Nations sanctions banning the supply of arms to Iran, the fulfillment of the contract was postponed. In 2016, Moscow began using the Iranian airbase in Hamadan for its Syrian operation. Later, the Iranian Defense Ministry leadership criticized Russia for disclosing this information. Russia and Iran, having large oil and gas reserves, are direct competitors for supply markets in the energy sector. Also, despite their common goals on the Syrian track (preserving the current government, combating terrorism, and restoring the territorial integrity of Syria) while maintaining allied relations, Moscow and Tehran continue to compete for areas of influence. Usually, the competition relates to involvement in the development of energy resources. The two sides continue to disagree over countering Israeli strikes on Syrian territory.

Where do interests in the South Caucasus coincide?

If Iranian and Russian interests coincide in different regions, they usually have a strategic dimension, such as in the Syrian context. Moscow and Tehran have historically been competitors for a zone of influence in the South Caucasus. Other centers of power have not challenged Russia’s dominance over the past centuries. However, the South Caucasus is now undergoing the most significant geopolitical shifts since the collapse of the Soviet Union. In this context, Tehran and Moscow have points of intersecting interests.

First, security issues. After the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, Russia and Iran acted as “status quo states” that were not interested in changing the new configuration. This position was formed against the background of the revisionist ambitions of Turkey and Azerbaijan, which eventually achieved unilateral concessions from Armenia through the use of force: the recognition of Artsakh as part of Azerbaijan with fallout of Nagorno-Karabakh, further ethnic cleansing and the surrender of territories in the Tavush region as a result of the “demarcation” process. Given these events, Russia no longer has a presence in Nagorno-Karabakh. It cannot provide the necessary assistance to Armenia, which has become more vulnerable with regard to security. Therefore, Armenia has had to start diversifying its foreign and security policies. For Iran, the threat of losing its border with Armenia has become more real. Before September 2023, Baku was projecting its military power against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh; after the fallout of Nagorno-Karabakh, Baku could concentrate all its military power against Yerevan.

Second, the development of vertical communications. With the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the issue of overcoming the economic blockade has become urgent for Russia. In this context, the International North-South Transport Corridor, designed to connect Russia and Iran via the South Caucasus, plays an important role. At the same time, in Armenia, Iranian companies Abad Rahan Pars International Group and Tunnel Sadd Ariana are engaged in the reconstruction of a 32km section of the Kajaran-Agarak road in Syunik, which is part of the “North-South” corridor. The works are funded by the budget of the Republic of Armenia, the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development, managed by the Eurasian Development Bank, in which Russia plays a leading role.

Third, regionalization of the South Caucasus with limited Western influence. As a result of the 2020 war, Russia lost its monopoly position, allowing Turkey to gain a foothold. Iran was kept out of the new configuration. It was not engaged in the post-2020 status quo, which included the deployment of a Russian peacekeeping contingent in Nagorno-Karabakh and the establishment of a joint Russian-Turkish monitoring center. A possible option for Iran’s involvement in regional processes at the diplomatic level is the “3+3” format (Armenia, Iran, Russia, Georgia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan). This format was initially initiated by Turkey and Azerbaijan, then actively supported by Russia, which sees it as an opportunity to de-Westernize the South Caucasus.

The main points of contradiction

As in the bilateral and Syrian tracks, the approaches of Russia and Iran to processes in the South Caucasus do not fully coincide and have profound contradictions. For example, in many ways, Iran interlinks the issues of security and communications in the region, while for Russia they are in different “baskets.”

This issue came to the fore after Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated in Baku in August 2024 that Armenia was sabotaging the implementation of Article 9 of the November 2020 Statement on unblocking communications. This statement was perceived in Yerevan and Tehran as an attempt by Moscow and Baku to pressure Armenia jointly. A series of active steps and messages from Tehran followed. The Russian Ambassador was invited to the Iranian Foreign Ministry. The so-called “Zangezur corridor” issue was put on the bilateral agenda, initially including mostly Russia–Iran Strategic Partnership Agreement points. The “corridor” was discussed during meetings in St. Petersburg, as well as during the visit of the Secretary of the Russian Security Council, Sergey Shoigu, during talks with the Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council of Iran, Ali Akbar Ahmadian. The Russian representative reiterated his support for Iran's policy regarding corridors and transportation routes with Azerbaijan, despite an earlier statement by the Russian Foreign Ministry that “Moscow assumes that Tehran has heard Moscow’s position on the Zangezur corridor.”

Russia has traditionally stated that the unblocking of regional communications should not occur within the framework of “corridor” logic. Still, it should be based on the principles of Armenia’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and jurisdiction. Moreover, against the background of active bilateral dialogue between Yerevan and Baku on normalizing relations, Moscow has been inactive for a year. However, after it became known that part of the responsibility for communications through Syunik might be transferred to an international private company (which will most probably be Western), Baku offered Moscow to become involved in the process based on Article 9 of the November 2020 Statement, which includes the deployment of Russian border guards. Any unblocking of communications that takes place outside of Armenia’s full sovereignty and territorial integrity is not acceptable to Iran. This approach comes from a fundamental understanding of Ankara’s and Baku’s goals in the region, which envisages at the initial stage the establishment of a direct land link between Turkey and Azerbaijan at the expense of Armenia’s territory. The negative result of Russia’s failure to control the communication that was within its area of responsibility is the blockade of the Lachin/Berdzor corridor by Azerbaijan and the subsequent complete removal of Russian peacekeepers. Therefore, no one can guarantee that in the medium term, communication through Syunik will not turn into a direct corridor—neither Russian border guards nor an international private company.

Therefore, Iran has two best options: to keep communications through Syunik closed or to unblock all communications in the region under Armenia’s full sovereignty. Moscow sees the situation differently: if Russia does not control the communications, it is highly likely that there will be a Western presence there, as happened with the EU mission, which Armenia preferred to the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) mission.

The positions of Russia and Iran also differ on Western presence in the South Caucasus. Amid Moscow’s harsh criticism of deploying the EU civilian monitoring mission in Armenia, Tehran has not voiced unambiguous negative assessments. Perhaps Tehran realizes the possibility that an EU mission can contribute to maintaining peace. A civilian mission of 209 non-armed personnel cannot deter the Azerbaijani army’s offensive; however, the EU mission managed at least twice to disavow disinformation from the Azerbaijani Defense Ministry that Armenian Armed Forces were pulling heavy equipment to the border. Usually, such statements are disseminated in preparation for provocation. After European observers stated that no movement of armed equipment toward the border had been recorded, the preparatory disinformation wave from Baku stopped.

In this context, Russian statements that the EU monitoring mission is engaged in gathering intelligence in Armenia against Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan are still coming out. It is important to emphasize two facts. First, the deployment of the two-month mission was initially discussed with the participation of the Azerbaijani side. Second, similar assessments that European observers are spying on Iran were not voiced at a high level from Tehran. This indicates a more balanced approach from the Iranians to the activity of the Europeans on the territory of Armenia. An explanation for this can be found in Iran’s red line regarding the presence of the West: it must not be permanent or military. The EU mission is temporary and civilian. Iran reacts more sharply to US presence and activity near its borders, as it does with the expanding Israeli presence in Azerbaijan.

***

In summary, the difference in approaches to the EU mission, where Russia has greater concerns than Iran, contrasts diametrically with the so-called “Zangezur corridor.” Iran sees this as a “Turan–NATO” corridor, which will lead to the strengthening of Turkey’s destructive pan-Turkish aspirations for the region and the consolidation of NATO in the region. Such assessments are not coming from Russia. In this sense, Iran is more cautious about obvious threats, as they are formed strictly at its border and directed against national security. From this perspective, Russia misperceives Turkey as an extension of NATO and a revisionist state that uses pan-Turkish narratives to gain a foothold in the Middle East, South Caucasus, and Central Asia.

Despite some differences in approach, the course for improving relations between the two countries remains on track. The strategic partnership agreement will create a basis for dialogue on a broader agenda. It will probably be more difficult for Moscow to ignore Tehran’s justified concerns, especially with regard to its borders.

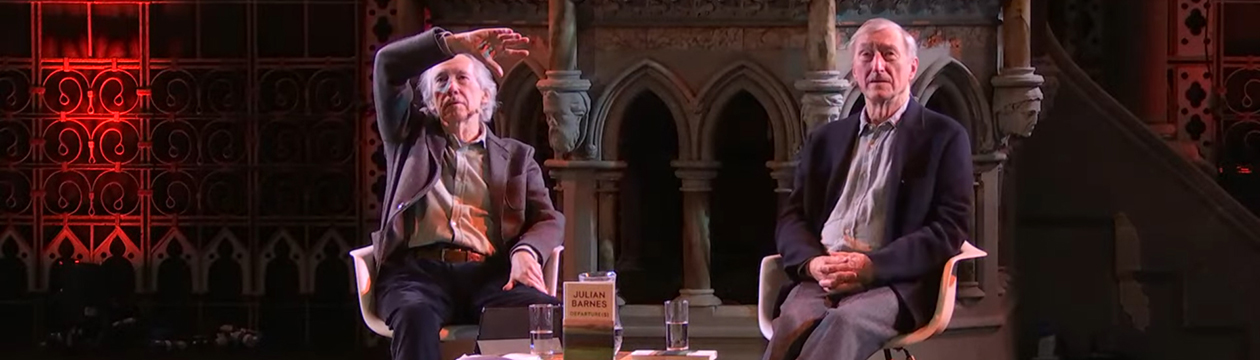

Sergei Melkonian, Ph.D., Research Fellow, APRI Armenia.

These views are his own.