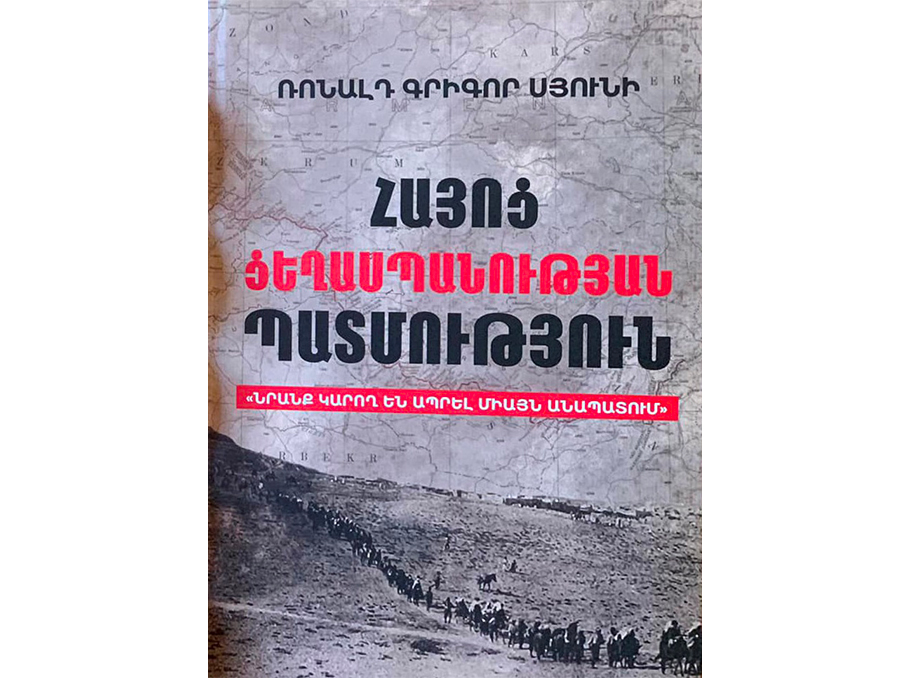

In the fall of 2022, “Magaghat” publishing house presented Ronald Grigor Suny’s “The History of the Armenian Genocide” (“They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else”) in the Armenian, translated by Maria Sadoyan.

Mediamax spoke with the author and the translator of the book.

Ronald Grigor Suny: “It is very important to me to have an Armenian translation of my book”

Is it important to you to have the book translated into Armenian?

It is very important to me to have an Armenian translation of my book on the Genocide. It has already been translated into Turkish (by an Armenian press in Istanbul) and Hungarian, so an Armenian translation will bring it to the most important audience of all to read about the most tragic event in the long history of Armenians.

Because it is a scholarly book by a professional historian, and not driven by nationalism or narcissism, this book has upset many Armenians in the diaspora for trying to explain why the Young Turks, Kurds, and ordinary people turned to mass murder of their neighbors. I have been told it is not necessary to try to “explain” the Genocide because this can lead to rationalization and even justification of what the Ottomans did to Armenians and Assyrians in 1915-1916.

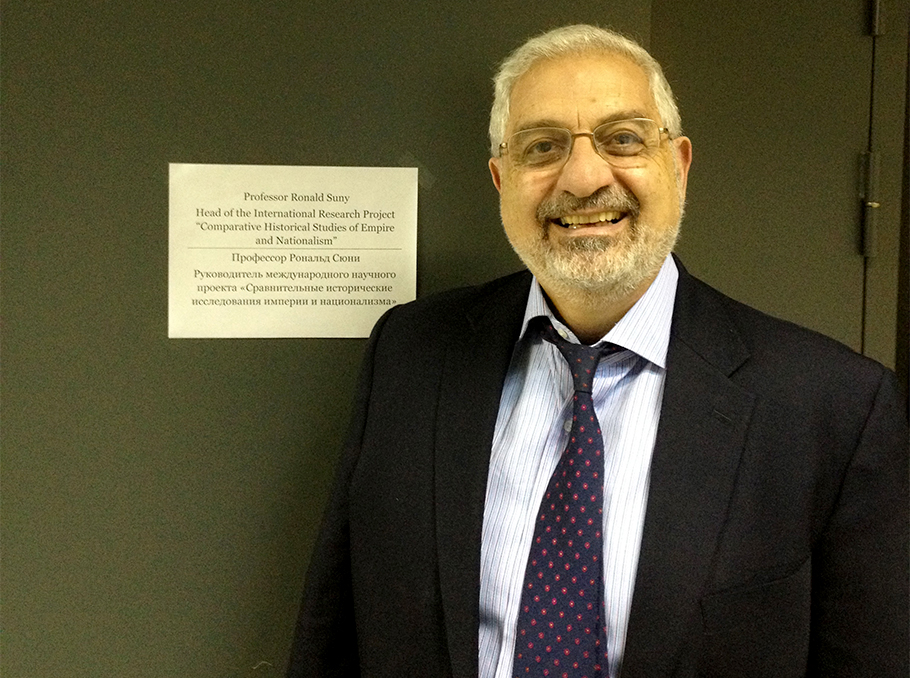

Ronald Grigor Suny

Ronald Grigor SunyBut without explanation, one cannot understand the causes of the tragedy, which are complex and deeply influenced by the long history of Ottoman treatment of non-Muslim peoples, international rivalries and the ambitions of the Great Powers, and the efforts by Armenian revolutionaries to protect their people and achieve some degree of power within the Ottoman Empire.

My hope is that this book will inspire others to delve deeply into this horrific moment in our history and increase our knowledge of what happened and why.

When you write books, and this one in particular, do you think whether the reader will be American, Russian, German or Armenian? Is it important to you?

Whenever I write books and articles, I write for an informed audience - students, teachers, the interested public - of all nationalities, not specifically for Americans or Armenians. Of course, if the book is about the Genocide, I would like Armenians, Turks, and Kurds more than anyone else to read the book, and therefore I was very happy to have a Turkish translation and even more thrilled to have an Armenian one.

Armenia is going through hard times now and there are conflicting approaches. Some say that we have to “forget” our past and focus on our future and others insist that we can’t move forward without having a clear view on our past.

There is no forgetting of the past, though there can be better or worse understandings of the past. My hope is that this book will encourage complex, nuanced, informed thinking about the long history of Turks, Kurds, and Armenians living together, and not think of those long centuries of coexistence only from the perspective of their tragic end. It is very important that some of the perpetrators of the Genocide, the Kurds, today are themselves victims of the Turks, and they have come to recognize the Genocide and their role in it.

That is an amazing and hopeful development - that people can rethink history and learn new ways of living together. Armenians are fated to live in a dangerous neighborhood, with Azerbaijanis and Turks and Kurds living around them. Through learning about the past, and recognizing what happened, perhaps someday in the future that dangerous neighborhood will become secure, prosperous, and a haven for Armenians around the world.

Maria Sadoyan: “It’s time to talk about Genocide in a more comprehensive way”

Why did you decide to translate Ronald Suny’s “The History of the Armenian Genocide”?

I vividly remember the moment I decided to do it. There was a discussion on Twitter about which book on Genocide thoroughly and comprehensively covered the issue, and one of the western political analysts said that Suny’s “They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else” was perhaps the best in-depth book, both among scholars and readers, which, unfortunately, did not have an Armenian translation, although it had already been published in Turkish. It caught my attention right away.

Once I read the introduction, I realized that the book would differ from the common narrative about the Genocide we read in textbooks. This is not a collection of historical documents or personal memoirs and biographical sketches either. Unlike previous studies that described how the crime happened, this work is an attempt to understand why it happened, which appealed to me the most.

Masha Sadoyan

Masha Sadoyan“They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else” (a quote from Talat Pasha, who said these words to Henry Morgenthau, the US Ambassador to Turkey) is a chronicle based on archival documents and eyewitness testimony. Step by step, Suny analyzes the history of Armenian-Turkish relations and the geopolitical and ethno-psychological situation that had led to that dreadful moment when the Ottoman government decided to deport and exterminate the Armenian population of the Empire, along with several other peoples. The book is an attempt at revealing the roots of the mentality of Young Turks who committed this atrocity, the ideology that allowed the Ottoman leaders and their followers to perceive Armenians as a deadly threat to the Turkish state and the Turkish people.

You must know that many representatives of the “traditional” historical school in Armenia have a different approach to Ronald Suny and his works. Did it bother you?

Quite the opposite, it encouraged me. I think we need to see our history less emotionally, put it in perspective so to say.

Suny explores two separate, conflicting accounts of the event. One is the denial of the Genocide by the Turks, who portray the pogroms as a rational response to a rebellious, treacherous population that threatened the survival of their state. The other is Armenia’s description of the tragedy as a fierce and inhumane determination of the Turkish Muslims to exterminate the non-Muslim population of the Empire.

Digging up the archives, Suny finds the rejection of the Turks ridiculous: “There was no Genocide, and Armenians are the ones at fault”. However, he also thinks that the Armenian Genocide was not a long planned and carefully implemented idea, but a vengeful thought born under the influence of geopolitical events, particularly the World War I, which unfortunately became part of a state policy.

For this point of view, Suny was harshly criticized by his fellow historians. He counters, saying that Armenian historians are not willing to try to explain what happened. Maybe they fear that to explain will mean to rationalize the crime of the Young Turks and even to try to justify it. Besides, Armenian scholars do not want to change the accepted narrative. Suny, however, believes that to explain means to understand and to prevent it in the future.

When negotiating with Magaghat publishing house, we had a common vision: it is time to talk about the Genocide in a more comprehensive way, and the opposing approach should be a subject of discussion.

Were you in contact with the author while translating the book?

Unfortunately, not in person. However, I have heard of him during my years of studying international relations. He is the distinguished University Professor of History and Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan and Emeritus Professor of Political Science and History at the University of Chicago, which has been ranked among the best and most selective universities in the United States. His intellectual interests have centered on the history of the twentieth-century Russia and the USSR, especially the Caucasus region, ethnic conflicts and nationalism. He is the author of numerous books and scientific works, which, I think, would be also wonderful to translate into Armenian.

By the way, Suny is a descendant of Genocide survivors. He was born in 1940 in Philadelphia, his grandparents escaped Turkey after the massacres of 1894-1896 and 1909. Their other relatives were massacred.

What is so important about this book, especially today, when our future seems as controversial and vague as our past?

Suny, like Hrant Dink, is an advocate of Armenian-Turkish reconciliation. He believes that the reconciliation of two nations, who have lived side by side for ages, requires recognition of the joint history and mutual sufferings and a sober view of those bloody pages of the Ottoman Empire. To form this view, he believes, academic cooperation is of primary importance. Therefore, he, together with Zhirayr Liparityan and Fatma Muge Gocek, founded a Workshop for Armenian/Turkish Scholarship. Along with Gocek, he was awarded the Academic Freedom Award by the Middle East Studies Association for their work in bringing Armenian and Turkish scholars together to further study of the Armenian Genocide.

Looking to the future, Suny thinks the negative stance of Turkish officials no longer plays any role. “We are now in a situation where most sensible people, anyone who is thoroughly investigating these events, understands that the terrible tragedy that occurred certainly fits any reasonable definition of “genocide”,” he says.

Suny is optimistic: “Turkish people are ahead of their own government. Historians, sociologists, archaeologists and other scholars have already understood the 1915 Genocide, and Turkish journalists, students and professors have exposed the horrific events that accompanied the end of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey. The Kurds living in Turkey, who represent millions of dissident voices, have long recognized the Genocide in which their great-grandfathers were involved. Advanced Turkish intellectuals organized conferences, published books, wrote articles and spoke in public to open the dark pages of the Turkish past.”

Thus, the purpose of this book is to provide such an accurate and thorough analysis of the history of the Genocide, thanks to which Turks, Kurds, Armenians and other peoples will be able to see the events without a nationalistic and political veil and, as German Chancellor Angela Merkel once urged Recep Tayyip Erdogan to do - to “reconcile” with the history of their own country.

What is your biggest impression from the book as a reader?

I am not an expert on Genocide, but I was first of all impressed by rare archival materials that I came across while reading the book. It sends a chill down your spine when you read, for example, how during one of the meetings, Talat said to Ambassador Morgenthau: “No Armenian... can be our friend after what we did to them.”

As an expert in international relations, it was very important to me to see the phenomenon of the Genocide from a geopolitical point of view, to understand the developments in the region and to see their connection. It is also interesting to draw parallels between the differences between the Armenians living in Turkey and Russia back then and the Armenians living in Karabakh, Armenia and the Diaspora today.

As The Financial Times wrote, the book is terrifyingly detailed and maximally objective. Suny’s language is easy and attractive, which, I hope, the Armenian reader will appreciate, too.

Ara Tadevosyan talked to Ronald Grigor Suny and Maria Sadoyan