The spherical shrub with yellow flowers and small white fruits is omela, the mistletoe. They say the land is blessed and people are happy where this evergreen plant grows. There are many bushes of happiness in Tsmakahogh village of Martakert region of Artsakh. It is hard to say, though, how much they made the people of the genuine and hospitable village happy.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

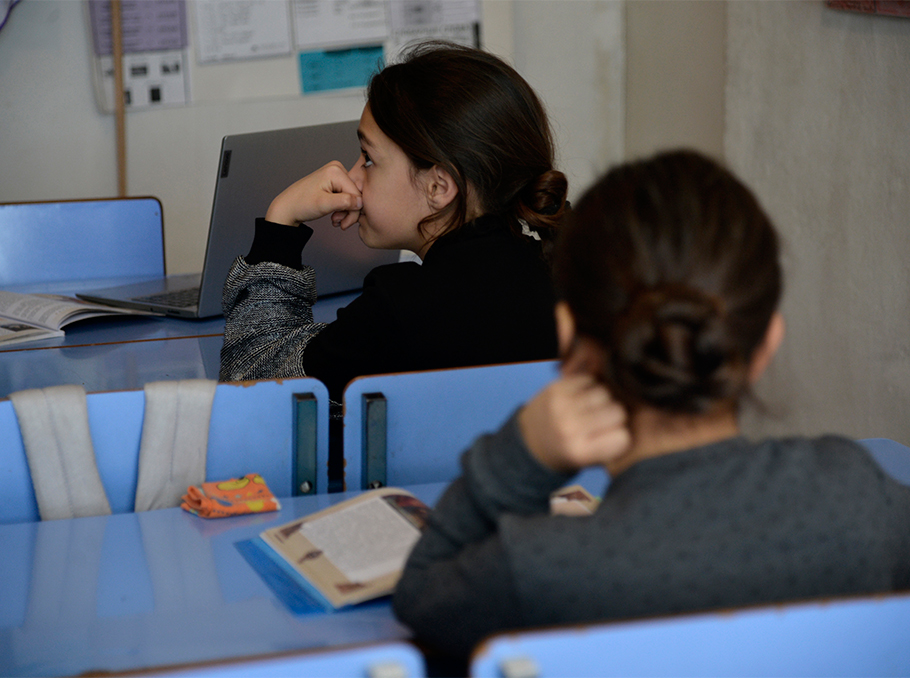

Ten residents of Tsmakahogh were killed in the first Artsakh war, and 3 in the recent one. Fortunately, the village was not damaged, and the residents have mostly returned. Three families that lost their homes have also moved to Tsmakahogh, and the number of school students has sharply increased; 28 children study in a well-maintained, clean and warm school.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

Speaking about the number of school students, the principal says it keeps decreasing rather than increasing. Young people get married and leave the village because there are no jobs here. They move to Martakert, Stepanakert, or to Armenia and Russia.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

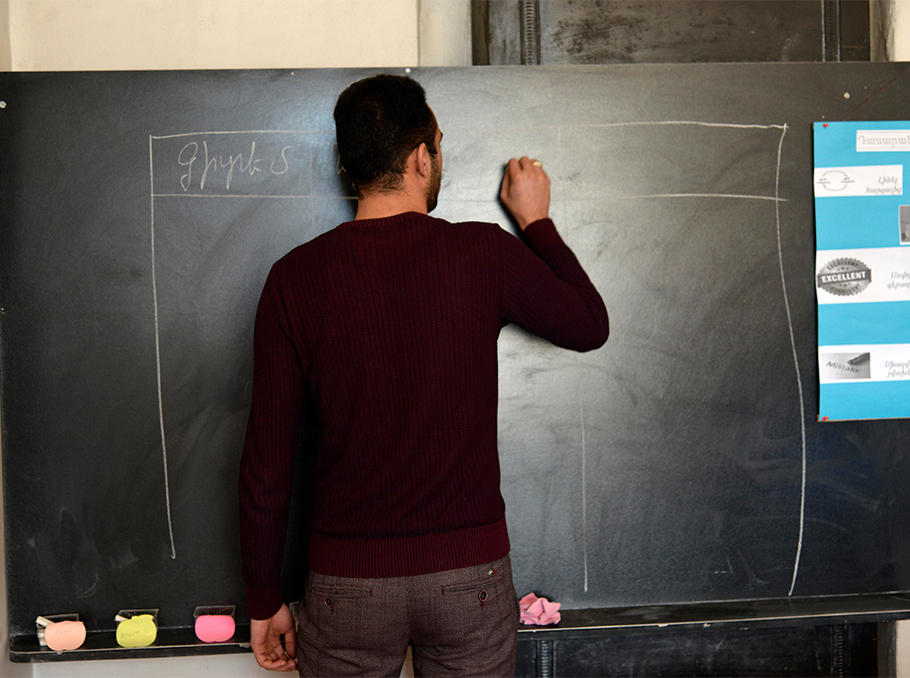

But there are also young people who come to Tsmakahogh for work, like for example from Gyumri.

“I was interested in Artsakh. Besides, coming here is a necessity. If we have a chance to come and do something good, each and every one of us should do it. This is how I thought and came to Artsakh to teach.”

Artur Kirakosyan

Artur Kirakosyan Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

Artur Kirakosyan is a pedagogue, but he has never worked in his profession. He thought it was hard for an inexperienced young man to work with a large class. He read several stories online about teachers working in the villages of Artsakh and Armenia within Teach For Armenia Leadership Development Program. “It caught my interest. Despite all the difficulties, it is a beautiful life, a life test.” And unexpectedly for him, he applied to the program.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

When he moved to Tsmakahogh in August, life was happier and more colorful. He had been teaching for two weeks when the war broke out. On the eve, they were talking about the possibility of war at school. So, when early in the morning on September 27, one of the teachers called him after the first explosion and said to leave the house because a war had begun, he thought they were joking. The third explosion shook the house.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

“I was hesitant to leave. I never served in the army, so I would have been useless with a weapon, but my heart was in the village. People’s feelings were like a heavy burden on my soul. I have never seen war and I couldn’t even imagine what it looked like. I walked around the village, people were crying outside their houses, the children were in panic. It affected me a lot, making me emotionally depressed, but I didn’t show my feelings because there were children with us. We decided to leave the village.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

After returning to Armenia, I couldn’t come to terms with myself, especially because one of my students, a girl, was still back in the village, and I felt responsible for her. I kept saying it was wrong that I had left my student there. It was a spontaneous decision.”

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

If not for the war, it would have probably taken weeks for Artur to get to know his students and make friends with them. The war quickly brought them closer. He found 10 of his students right after returning to Armenia, and every day he talked to them about their worries and fears, sometimes for hours.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

When the chance arose to return to Artsakh, Arthur didn’t hesitate long.

“When I talked with the children, they would always ask me if I would return to the village with them. I promised them I would be back and I couldn’t break my word. I had no right to disappoint them. It was a huge responsibility. And I understood it when the principal asked me if I was going back to the village. There is a shortage of teachers in Artsakh today, many schools have closed down, and the teachers are unemployed. They may have not asked me to come back, but they did, and I felt that I was needed. Once I got back to Artsakh, I felt at peace.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

Teach For Armenia has an ideology called “Kochari”, which says that we must move forward hand in hand, in proportionate steps. I am part of that chain. If I hadn’t returned, I would have broken the chain. If I have decided to come here from Gyumri, then I must stay true to my oath till the end, do my job, be useful to my children.”

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

Artur had many fears when he first stepped foot in school back in September. Fortunately, he did not encounter major problems. The students have eagerly welcomed him, the principal and the teachers were a big help. However, education has also suffered from the war. Today, just like in September, Arthur is trying to inspire the students and arouse their interest.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

“A long time has passed since the war, but the children can’t focus on classes. Knowledge is important, but now I want them to open up, forget their worries and get back to things. Their psychological stability is the most important thing for me. As for the classes, we will catch up in no time.

Artur teaches three subjects: Armenian History, World History and History of the Armenian Church. He does his best so that the children can get a good education. But, he says, his task is not only to teach but to help children discover and develop their potential.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

“Why did you like the lesson? Was it difficult? What would you change? Would you like me to explain another way?,” these are the questions Artur usually asks his students at the end of the class.

- We have made a special box together, and at the end of the class, we write down what we have learned and what we want to know on a piece of paper and put it in the box. During the next lesson, the teacher opens the box and answers our questions, - says one of the 5-grade students.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

The teacher’s house is on the territory of the school. The two-room house used to be a cafeteria, and is now the best place for him to stay. The school yard is usually crowded even after the school lets out, and there is no chance to have a quiet minute, nevertheless Artur doesn’t complain. It gives him more time with the children.

“When they want to come out here to play, one of the adults should always be here so that they don’t harm themselves, and when everyone is busy, I do it myself. That’s why they tell me “friend, we love you” in Gyumri dialect.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

I always keep a big box of candies for them. There was this one time when I was not home, they were playing in the yard, got hungry and ate all the candies. Then they told their families they had eaten all my candies.

Everyone in the village knows Artur and often invites him over. He visits with the villagers, especially when the electricity and internet are off in the village.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

About 230 people live in Tsmakahogh. They are mainly engaged in agriculture and cattle breeding. When they talk about their village, they start with stories about fellow villager, famous engineer and physicist Andranik Iosifyan, scientist in the field of electrical and aerospace engineering. During the World War II, the author of over 30 inventions was the head of a military factory producing weapons and ammunition, the chief constructor of electrical equipment of ballistic rockets, nuclear submarines and spacecraft. His activity was kept secret in Soviet times.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

“Iosifyan brought Valentina Tereshkova to our village. He also donated the first TV set and the first car to the village. Our village was the first in Karabakh to have electivity. He has made everything for the village,” says Spartak Avanesyan, the principal of the school named after the scientist.

The villagers say that Iosifyan used to visit Tsmakahogh in the summer, often with foreign scientists and students. They remember how he would come to the village, change his shoes and ride a horse. A part of his hospitable house will become a museum.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

Today, the scientist’s nephew, his brother’s son, Aram Iosifyan, lives in the house. He is a lawyer, and moved to Tsmakahogh from Moscow in December after the war.

“I took the war losses very hard. I thought we should come and slowly bring Artsakh to live. I met with some officials and told them I was ready to help however I could, with my education, knowledge and experience. It doesn’t matter whether I’ll be paid or not. What is more important is that I do something useful and interesting.”

Lusine Gharibyan talks to Aram Iosifyan

Lusine Gharibyan talks to Aram IosifyanPhoto: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

The day we met Aram Iosifyan, he was grazing his and his fellow villagers’ sheep for the first time. He has 5 sheep so far. There is a rule in the village: for every 5 sheep they own, each farmer takes the sheep of the whole village to the pasture for one day. “Here they say “ochered”, which means “turn”. Today is my “ochered”, my turn,” Aram says smiling.

Although he spent his childhood in the village, he doesn’t remember much. He is now rediscovering Tsmakahogh again.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

“There comes an age when you realize that everything is futile - cars, money, luxurious houses. Honestly. I take pictures of the nature and mountains of Tsmakahogh and send them to my friends in Moscow. “We are so jealous. We would leave everything and come to the village in a heartbeat if we could,” they say.

Andranik Iosifyan’s another nephew, his sister’s son, Professor Vladik Avetisov, is also planning to move to Tsmakahogh. They have both initiated the opening of the scientist’s house-museum, and also intend to restore the Mamkan Church of the 12th-13th centuries.

Photo: Vaghinak Ghazaryan/Mediamax

Tsmakahogh is a busy place especially in the summer. A tent school-camp for young naturalists has been held in the village for years, with the participation of students from the communities of Artsakh, and sometimes from Yerevan too. Professors from Artsakh, Yerevan and Moscow universities come to teach during the camp. The camp was not held in 2020 due to the global pandemic.

Artur hopes that nothing will hinder them from holding the camp this year and he will have a chance to take part in this event of Tsmakahogh, and it is OK that he will have only one week in the summer to return to Gyumri and see his relatives.

Lusine Gharibyan

Photos by Vaghinak Ghazaryan (especially for Mediamax)

Comments

Dear visitors, You can place your opinion on the material using your Facebook account. Please, be polite and follow our simple rules: you are not allowed to make off - topic comments, place advertisements, use abusive and filthy language. The editorial staff reserves the right to moderate and delete comments in case of breach of the rules.