In the classroom, the professor announces the assignment to check how well the students have learned the course material. Instead of filming a short 5-minute video about Turkey, the country they have covered during the term, fellow students Artyom Vanian and Hrant Yeritskinyan buy tickets and travel to Istanbul. They tour the Armenian neighborhoods of Istanbul, talk to the local Armenian population, and end up shooting a documentary film “Beyond the Silence: Armenians in Istanbul. A Glimpse into a Legacy”.

In an interview with Mediamax, Director Hrant Yeritskinyan and expert on international relations Artyom Vanian reminisced on their trip to Istanbul, discoveries they have made, and the upcoming new film.

A serious journey born from a joke

Director Hrant Yeritskinyan returned to Yerevan from Canada to join a Master of Arts Program in International Relations and Diplomacy (MAIRD) at the American University of Armenia. Artyom Vanian, who also moved to Yerevan from Moscow, also studies MAIRD at AUA. They both intend to stay in Armenia.

One of the most interesting courses this year is the Caucasus Regional Politics taught by Professor Vahram Ter-Matevosyan. The first module of the course provided insight into the strategy of the Republic of Turkey.

Artyom Vanian

Artyom VanianPhoto: Mediamax

“As part of the course, we were supposed to shoot a 5-minute video in which we had to talk to each other about Turkey using our negotiation skills. I jokingly said to Hrant that we should travel to Istanbul and I would show him around. He agreed, so we quickly bought tickets and left for Istanbul on March 20,” says Artyom.

Artyom received his first degree in international relations from the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, and his primary focus during his studies was on Turkey. Because of this, and also because he has been to Istanbul before, Artyom has thoroughly planned their 5-day stay in Istanbul.

Suleymaniye Mosque

Suleymaniye MosquePhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

“Artyom’s planning made my job as a director a lot easier, so I knew right away what and where I would film. Initially, I intended to do serious filming, but after giving it some thought I realized that I wouldn’t see anything that way. Usually, after filming I am often asked if I remember this or that episode, and I say if it’s not on my camera, then I don’t remember,” Hrant says laughing. In the end, they decided to only use an iPhone.

Hrant Yeritskinyan

Hrant YeritskinyanPhoto: Mediamax

During a tour of Istanbul and meetings with local Armenians, Hrant kept thinking that this specific episode should also be filmed. Each subsequent episode seemed more interesting than the previous one. This is how they ended up with enough material for a full-fledged documentary.

The legend of Kör Agop (blind Hakob) and the Island of Armenians

During their first day in Istanbul, Hrant and Artyom visited the non-Armenian monuments of the city, and on the second day they toured the Gum Gapu neighborhood (historical Kontoskalion), visiting the Bezdjian Mother College, the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, the Mother Cathedral of the Holy Mother of God (Surp Asdvadzadzin Patriarchal Church), as well as Surb Harutyun Church.

Bezdjian Mother College

Bezdjian Mother CollegePhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

“Gum Gapu used to be a very wealthy Armenian neighborhood, but now it is mainly populated by immigrants from different countries,” says Artyom.

They met a local Armenian who organized a tour of the neighborhood, showing them its Armenian character.

“There used to be many fish restaurants in the district. The local Armenian resident who was accompanying us said that the first fish restaurant founded there was Kör Agop’s Restaurant (blind Hakob), after which new fish restaurants opened in the area. But this information needs to be verified,” says Hrant with a smile.

Kör Agop’s Restaurant

Kör Agop’s RestaurantPhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

They also visited Kinaliada, a Princes’ Island near Istanbul, which is considered an Armenian island. Artyom says people don’t live there anymore, and Armenians mainly use their houses during the summer months.

“As soon as we got off the boat, we glanced through the window of a private house and read a framed inscription “Glory to God” inside the house,” says Hrant, noting that this episode was included in the film.

St. Gregory the Illuminator Church on Kinaliada Island

St. Gregory the Illuminator Church on Kinaliada IslandPhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

“Then we walked through the Hrant Dink Park. The restaurant we dined at was called “Dinner,” then we passed by the “Saprich” barbershop, and also visited St. Gregory the Illuminator Church on the island,” said Hrant.

“The new generation of Turks should know who Armenians are”

According to Artyom, there were many medieval churches in each of the districts they visited. Unfortunately, liturgy is rarely served in those churches, since there are few Armenians left.

Holy Mother of God Cathedral of Constantinople Istanbul

Holy Mother of God Cathedral of Constantinople IstanbulPhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

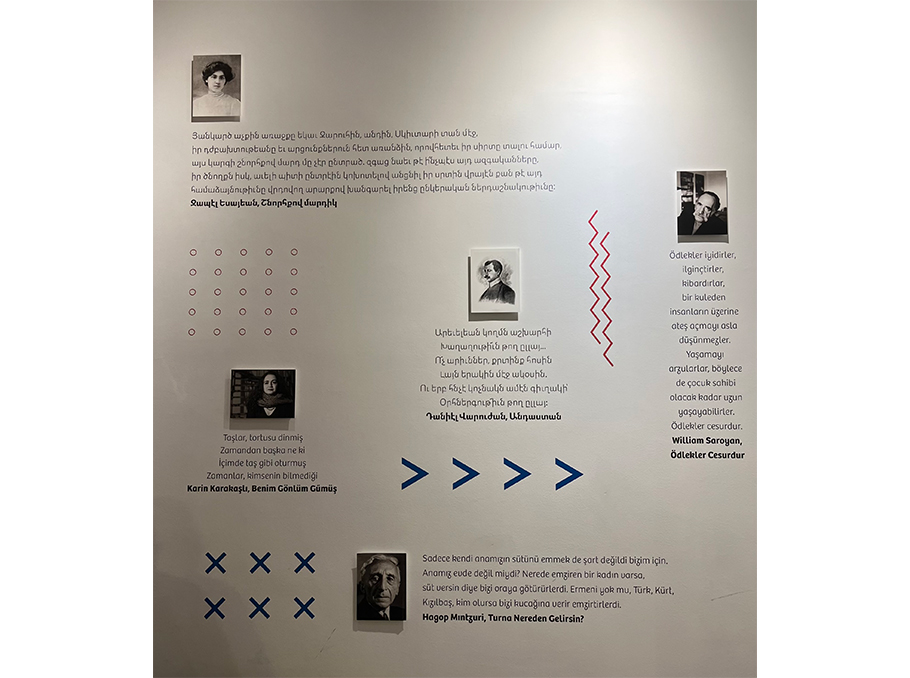

While strolling through Beyoglu district (historical Pera), the friends visited the “Aras” Publishing House. One of the most important mission of the Publishing House is translating Armenian books into Turkish.

“We met an Armenian doctor at the publishing house, who is featured in our film. He said that the new generation of Turkey should know who Armenians are. The previous generation knows the Armenians, has learned from them, understands the role and significance of Armenians in the local society, while the new generation is not familiar with the Armenians. In this sense, “Aras” Publishing House is doing a great job,” says Hrant.

Aras Publishing House

Aras Publishing HousePhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

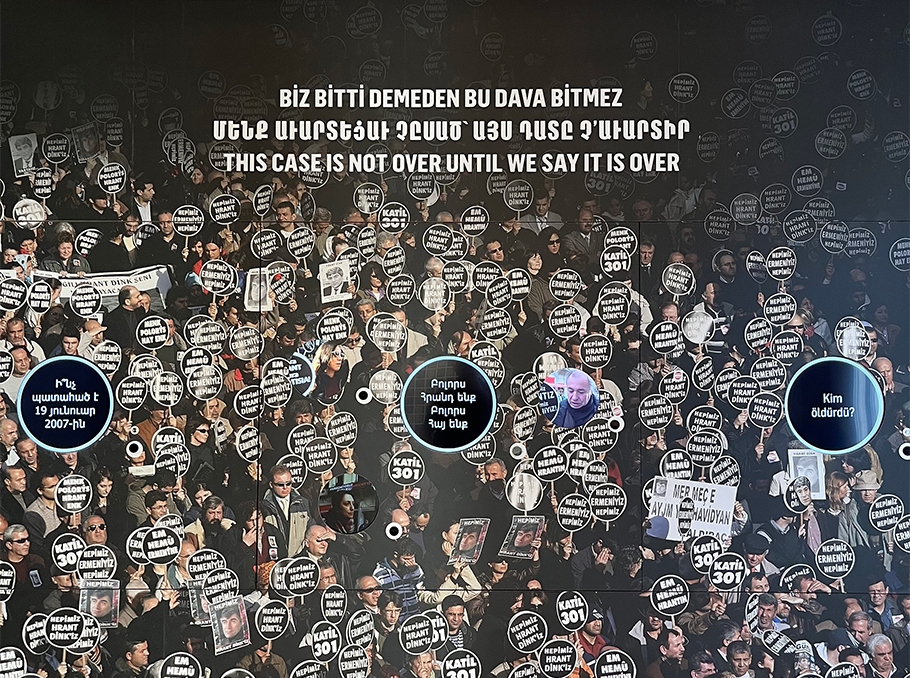

While in Istanbul, it was very easy for Hrant Yeritskinyan to introduce himself; his name is well-known to everyone. The last day of their visit was dedicated to visiting the Hrant Dink Foundation and the Hrant Dink “23.5” Site of Memory, where they learned about the Foundation’s extensive work aimed at showcasing Armenian culture and spreading Hrant Dink’s ideology.

“Zhamanag’s” guest scholars

The last place Artyom and Hrant visited was the editorial office of “Zhamanag” (The Times) newspaper. After a short tour and a meeting with the editor-in-chief Ara Gochunian, they left the editorial office with a funny surprise.

A typical house on Kinaliada Island

A typical house on Kinaliada IslandPhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

As we were about to leave the editorial office, Ara Gochunian stopped us to take our picture. We thought it was just a photo to remember our visit, but when we asked him to give us an issue of the newspaper as a souvenir, he said: “You will be in tomorrow’s issue, so you will take it with you.” At first, we didn’t quite understand what he meant. We were leaving the next day, so we woke up early to buy the latest issue of the newspaper.

Photo: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

And indeed, we were on the front page of the newspaper, and the headline read: “Guests in my editorial office.” We were introduced as “two Armenian scholars from Canada and Russia,” Hrant recalls with a laugh, adding that although everything in the article was written correctly, they were surprised by the attention and the word “scholars.”

Multifaceted merchants

The man speaking in the early minutes of the film is the manager of the hotel Artyom and Hrant were staying at. Hrant learned that this man was half Azerbaijani only during the filming.

“He behaved like an Istanbul native. He told me that when he was little, his grandmother taught him that Armenians were enemies and how his grandfather had killed Armenians. He knew history well and said that the Muslims came to drive out the Christians. He spoke in such a way that it seemed that everybody would have done the same. He was presenting historical facts without any judgment,” recalls Hrant.

Artyom says that he was speaking to an Armenian this way, but he might have spoken to an Azerbaijani in a completely different way.

National Central College of Istanbul

National Central College of Istanbul Photo: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

“The behavior of Turkish merchants resembles Turkey’s policy. If a Russian comes by, they become pro-Russian, if a German comes by, they become pro-German, if an Armenian stops by, they either become Armenian, or turn out to have Armenian friends,” says Artyom, describing another frequently encountered situation.

“When I was buying a ticket to the Hagia Sophia, the ticket office employee probably guessed from my accent that I was not a local. First, he asked if I was Azerbaijani, I said no, then he asked if I was Armenian, I said yes, after which he immediately added that his grandmother was also Armenian. This is a frequent occurrence. Merchants say that the Turks immediately become Armenian to boost their trade. In such cases, they usually say that their females are half Armenian, and no one asks where the men have disappeared to. While it is quite likely that many of these people have Armenian roots, such answers should always be treated with suspicion.”

Armenians living in the grey area

Thanks to the tour, Artyom and Hrant made interesting discoveries for themselves, meeting and talking not only with native Armenians, but also with those who moved from Armenia to Turkey in the early 1990s.

Hrant Dink’s Office

Hrant Dink’s OfficePhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

“These people came to Turkey to work. Most of them are merchants. They have no documents and live in a ‘grey area,” says Hrant.

According to Artyom Vanian, Turkish politicians often speculate about the number of Armenian immigrants living in Turkey.

In 2000, former Turkish Prime Minister and Turkish National Assembly member Tansu Çiller mentioned 30,000 Armenian immigrants living in Turkey, declaring that they should be deported. In 2005, speaking about Armenian immigrants, then-Turkish Foreign Minister Abdullah Gül cited a figure of 40,000, and in 2007, he cited a different figure: 70,000.

Artyom Vanian

Artyom VanianPhoto: Mediamax

“In 2010, then Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan threatened to deport 100,000 illegal Armenian immigrants in response to the adoption of resolutions by the US and Swedish authorities recognizing the Armenian Genocide. According to some sources, the data was provided to Erdogan by an influential member of the Armenian community, Petros Shirinoglu, who later admitted that the data was incorrect and said that the number of Armenians illegally living in Turkey was actually 20,000,” says Artyom.

The number of native Armenians who are Turkish citizens is also unclear.

“Based on a number of facts, it can be assumed that the number of Turkish citizens openly identifying as Armenian-Christians ranges between 40 000 and 70,000, the vast majority of whom live in Istanbul.”

Hrant Dink Memorial Museum

Hrant Dink Memorial MuseumPhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

Artyom and Hrant plan another trip to Istanbul in July-August 2025 to shoot a new film about the Armenians who came to Turkey from Armenia and live there without legal status.

“These people follow the news coming from Armenia, but they do not seem to belong anywhere. There are cultural differences with the Armenians of Istanbul, which is why they have not integrated into the community, and in Armenia they are looked down upon for living and working in Turkey. Many of them cannot even go back, as they have to pay huge fines they cannot afford,” says Hrant. Due to the lack of documents, these people’s children cannot apply to educational institutions.

Hrant Yeritskinyan

Hrant YeritskinyanPhoto: Mediamax

“During our tour of Istanbul, we learned that the Hrant Dink Foundation helped create schools where students study according to the Armenian school curriculum without having to present documents, so that later, when they have the chance, they can receive some certificate in Armenia,” he notes.

Artyom and Hrant have already found their heroes living in the “grey area”, so the friends want to make their voices heard, without harming them and hiding their identity.

“In Armenia, we seem to ignore the fact that these people exist. I understand that it is their decision, but I believe that we need to talk about them, their voices need to be conveyed to Armenia and the world because right now these Armenians are in an extremely vulnerable condition,” says Hrant.

Armenian “Surb Prkich” (Holy Savior) Hospital of Istanbul

Armenian “Surb Prkich” (Holy Savior) Hospital of IstanbulPhoto: from Hrant and Artyom's archive

After various conversations with Armenian immigrants, Hrant Yeritskinyan got the impression that their fear is expressed in the absence of fear. “For undocumented people, they sounded very confident, often praising the Turkish government and saying that they lived very well there. Of course, it is clear that this position directly stems from their vulnerable status,” says Hrant.

“We also want to understand these people, their lifestyle,” adds Artyom.

Hrant and Artyom’s first film was very well received by the Armenians of Istanbul, and they also received excellent grades for their assignment. With the second film, Artyom and Hrant will try to continue telling the stories of the Armenians of Istanbul that go beyond the silence, forming a dialogue with Armenian memory, but also about the life that goes on but “hangs in the air.”

Gaiane Yenokian

Comments

Dear visitors, You can place your opinion on the material using your Facebook account. Please, be polite and follow our simple rules: you are not allowed to make off - topic comments, place advertisements, use abusive and filthy language. The editorial staff reserves the right to moderate and delete comments in case of breach of the rules.