As we turn more and more to AI to search, organize, analyze, create – and sometimes even think on our behalf – a deeper question quietly emerges: Could this eventually make us less human?

To understand how our brains are navigating the rapid pace of technological change and the daily emergence of new AI tools, Mediamax spoke with Dr. Nikolaos Dimitriadis – an award-winning communications expert, Professor of Practice at University of York Europe Campus CITY (as of now, CITY College), where he leads the MSc in Neuromarketing.

Driven by his scientific pursuits, Dr. Dimitriadis has scanned over 9,000 brains across 25 countries to better understand empathy, leadership, and human behavior. In this interview, he offers a neuroscience-driven perspective on the very questions many quietly ask as we navigate emerging AI technologies, while also reminding us of what truly matters.

University of York Europe Campus CITY offers a wide range of undergraduate and postgraduate programs. Armenian applicants benefit from tuition discount system while gaining access to a high-quality British education through studies based in Thessaloniki, Greece.

In addition, the Pan-European Executive MBA program, jointly offered by the University of York Europe Campus and the Faculty of Economics and Management at the University of Strasbourg, provides Armenian applicants with the opportunity to receive high-quality British and European education and two MBA diplomas from York and Strasbourg Universities, while continuing to live, work, and study in Armenia.

- Professor, it is becoming increasingly common for people to consult AI language models as a first step when facing a task or question. What impact do you think this might have on how we think in the future?

- We need to remember that the human brain is adaptive. You have probably heard of neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to change. It involves four key processes. First is neurogenesis: between 600 and 2,000 new neurons are born every day. The second process is synaptogenesis: when we learn something – a new language, a musical instrument, or a task at work – new connections are created in the brain. Then comes the strengthening of existing synapses. And the last one is the weakening of synapses: things you have not used for a long time start to fade: the brain reduces the mass of those synapses because it no longer needs them. I think most people are afraid of this last one – the weakening of synapses – and wonder if we might lose some of our human abilities because of AI. And that will probably happen.

At the same time, though, we might form new synapses or strengthen existing ones, because we will also have to adapt to this new reality. As with every technology, AI will take some skills away from us, but it will give us others in return.

A recent article in Harvard Business Review found that the biggest growth in AI use is in therapy, companionship, and life planning. The study found that many people use AI to declutter their minds. As we live in an era overloaded with information, people talk about burnout and mental fatigue, maybe AI is what will help us cope with that.

It is too early to make conclusions but things will settle in a few years and it will definitely be a trade-off: we will win some and we will lose some. So, let’s see.

- Even though AI now handles an impressive part of work, many people often feel more mentally drained after using AI to assist in completing their tasks. In the past, doing some tasks ourselves gave us a sense of progress and energy through the process of creation, but it seems that AI is taking away much of that satisfaction. How do you explain this?

- At this stage, we are only beginning to understand how to work with AI – and AI itself is a vast world. There are so many tools and platforms out there.

Usually, when people criticize AI, they focus on large language models. But there are also specialized AI systems – agents – that can do fantastic work. We need to consider the full AI portfolio and what each tool is actually meant to do.

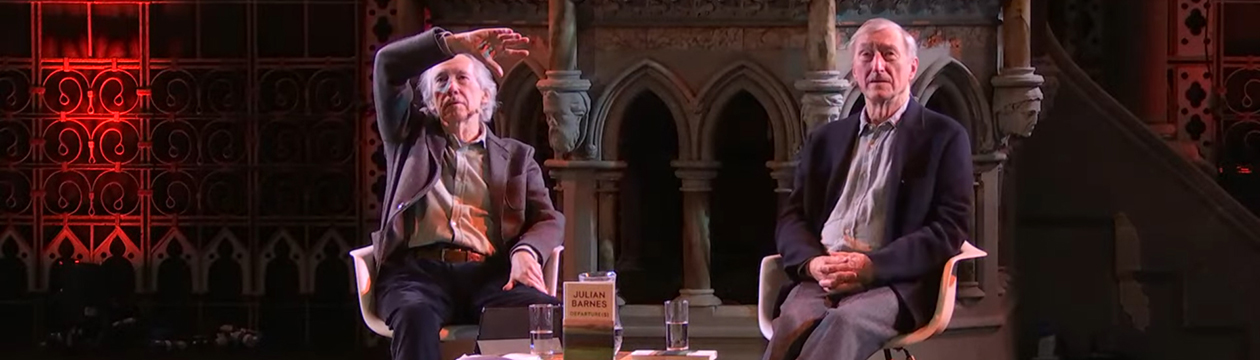

Nikolaos Dimitriadis

Nikolaos Dimitriadis Photo: personal archive

Right now, our brain is still experimenting with AI, trying to understand what this new thing is and how to set expectations. The brain works through prediction – it learns and anticipates in order to be better prepared. So the tiredness you mentioned may come from unmet expectations, lack of experience, or simply using the wrong tool.

As we progress, and as AI tools become more clearly defined in their use, I think the brain will adapt, and we will become much more efficient.

In my lectures around the world, I ask professionals how they use AI. The happiest are those using it for the core of their work. For instance, business lawyers in companies often tell me they use specialized agentic systems that really help them – just like having an intern. And I believe that is the right use of AI at the moment: as support that helps you organize, summarize, and handle the time-consuming legwork.

But when it comes to high-level cognition and strategic problem-solving, most executives tell me they do not expect AI to replace that. It can support it, but the final decision, and responsibility, remains with the human executive.

And the second area – which I would actually put first – is human relations. A big part of a manager’s role is talking to people, motivating them, understanding them, and even being a shoulder to cry on.

As for the other things that AI might replace – maybe that is a good thing. Maybe it will finally free us to focus on what truly matters. To me, it is actually the opposite of what most people say: maybe we are not entering the age of AI, but the real age of humans. As AI takes over the robotic tasks we have been doing, perhaps it is time for humans to shine.

- That is a great attitude – I love that. But I do worry that relying too much on AI, even for support, could make our brains lazy and dull our critical thinking. What kind of mental training should people consider to stay sharp?

- About a month ago, I wrote a post on LinkedIn that emerged to a big conversation on the fact that more than 50 percent of posts on LinkedIn are written with AI. I put a complaint that all the posts look the same – they look robotic, they have exactly the same language, the same emojis, the same structure, the same wording. Everybody speaks perfect English all of a sudden. Because of this, many people started not reading that posts, me included. Where am I going with this? I think that people using AI in a lazy way will be caught and socially punished. People that use AI in a lazy way, they look lazy and they cannot avoid that which will eventually bring to losing credibility. We even have a new term, cognitive offloading, to describe people outsourcing important aspects of their thinking, in lazy way, to AI. And cognitive offloading is already used negatively for people caught doing it!

Another thing is that being socially active maintains the sharpness of our brain, because with people, there is unpredictability, there are many levels of conversation and different people you have to adapt to. I also think companies should periodically revisit the role of AI to break the habit – just like you would conduct a performance review for an intern.

There are, of course, other things that every neuroscientist will tell you about how to keep your brain fresh: exercise, spend time in nature, eat less highly processed food, sleep well, have great relations. These five are very good. There are also other things one can do – like learning a new language, visiting new places, break few habits or even something as simple as brushing your teeth with your non-dominant hand. These kinds of things keep your brain more agile.

- I know that you are also an expert in how leaders can apply neuroscience to enhance their own performance and support their teams. It is a broad topic, of course, but could you share the general idea of how neuroscience can help to achieve leadership?

- Together with Professor Alexandros Psychogios, I co-authored a book titled “Neuroscience for Leaders”. In that book, we created a model called the Brain Adaptive Leadership Model, where we take neuroplasticity and brain adaptability as key aspects of leadership.

We live in an era where everything you want to achieve must be done with others. It is not a one-person show anymore. You need motivated, empowered, and engaged people around you. To make that happen, leaders need to work on four pillars – both in their own brain and in the brains of their team.

Nikolaos Dimitriadis

Nikolaos Dimitriadis Photo: personal archive

The first is cognitive: how you perceive reality, analyze it, make decisions, and handle information – the analytical side of the brain. Then comes emotions – the motivational engine. Next is behavior – your habits and how you typically approach work. And finally, relations – because we have a social brain, and relationships matter deeply to our brain.

So: Think, Feel, Do, Relate. Great leaders work across all of them. They have the right analytical processes to spot opportunities and threats. They manage their own emotions and influence the emotions of others. They shape behavior and habits – even small things like the day of the week you hold meetings or how your desk is positioned can shape outcomes. Leaders must create an environment that supports the right behaviors, and here physical space matters too. They also should they foster strong, collaborative, open – and yes, sometimes challenging – relations. Each pillar has its own science, its own tools, its own models.

- Let’s now turn to the field of education. There is an ongoing discussion about how to strike the right balance between technology and traditional teaching methods. In Armenia, for instance, some students from the Alpha generation appear to retain information better when it is delivered on a screen rather than by a teacher. Given these developments, what do you believe is the ideal balance to ensure effective learning?

- The phenomenon you mentioned is an example of brain adaptability. In my generation, we are digital migrants, whereas the new generation are actually natural inhabitants or natives of the digital world. Of course, their brains have adapted to deal with the new situation.

So yes, digital experience and digital learning will be a big part of future education. But we need to strategically design and insert human interaction moments.

Let me bring an example from another industry. When digital banking and mobile banking came along, many banks around the world believed that we would no longer need branches, that we would never see a banking employee again: everything would be done through your mobile app and chatbots. Although many parts are indeed handled digitally, people still need human connection. People tend to be more satisfied with their bank and remain more loyal to it depending on the human interaction they receive.

We will not shift to a purely digital way of education but will stick to blended learning. Data shows that human interaction, when it happens, has multiple effects on a person’s personality and resilience. And this is important as education is not only about knowledge. We do not send our kids to school just to learn history and mathematics. We send them to learn how to deal with other people, how to manage their emotions, how to interact with authority – the teacher, in this case. These are what we call social skills or emotional resilience. They will also be supported digitally, but we, by definition, need human interaction. So we need to understand which parts of education are better done on a screen, and which are better done through human interaction. And when we understand this better, I think we can design better learning environments. But human interaction will not be excluded. However small, it will play a very important strategic role.

- You lead the MSc in Neuromarketing at University of York Europe Campus (as of now, CITY College), where all programs emphasize critical thinking. Neuromarketing focuses on understanding and influencing human behavior, while critical thinking empowers individuals to question and resist such influence. Do you see a contradiction here?

- Great question – and the answer is surprisingly simple. The job of a marketeer is not to influence anybody in the sense of asking them to do something they do not want. Since the 1960s, the goal of marketing has been to discover people’s desires and give them more of what they already want. Marketing is about decoding emotions, desires, fears, and offering something meaningful and valuable.

Neuromarketing, specifically, measures the brain’s natural reactions – often unconscious. We use tools – eye tracking and electroencephalogram, for instance – to learn what the brain is drawn to, and then we respond to that. Even when we want to influence behavior – let’s say, to help someone stop smoking – we should understand their deeper fears and desires, find conflicting emotions that already exist (as we cannot create them out of nothing), and then give the message in that direction. For example: you like smoking, but you also have a small child, and you want to live more years to spend with your child.

In neuromarketing, we have very strong ethical and personal data protection laws. In order to be a neuromarketer, you have to follow the ethical code of neuromarketing and marketing research, as well as all the data protection laws of the EU or any other country you are in. This is a rule we do not negotiate. We teach this in my master's, by the way.

Nikolaos Dimitriadis

Nikolaos Dimitriadis Photo: personal archive

But of course, this kind of knowledge and data can also be misused. For example, social media is designed to make people addicted. It finds something that you already like, and by giving you more of what you want, makes you spend more and more time within the platform. I am afraid that AI systems, if run without regulation and ethics, might also misuse the data. And here again, we come to the importance of high-quality education, developing critical thinking, and having good advisors.

- In one of your interviews, you mentioned that the concept of technological singularity is largely a PR construct, particularly since humans are not born as a ‘tabula rasa.’ Do you believe this inherent difference will always create a divide between humans and AI, regardless of how advanced AI becomes or how much humans might degrade over time?

- In human terms, we have something called anthropomorphizing. That is when, for example, we see a rock that looks like a human face, or we see a dolphin and it seems to us as if it is smiling. We tend to attribute human characteristics to non-humans – animals or even objects. And this is a very important function of the brain.

Now, if you combine that with the human brain’s hardwired tendency to form relationships, you will understand why some people develop romantic relationships with ChatGPT. As I said, it is still too early to know whether this will persist or fade. But robots will become increasingly skilled at mimicking human behavior and our brains will take that because we have a deep need to connect.

People even say ‘thank you’ at the end of a ChatGPT session. And that is beautiful. It shows our humanity. Most people are good by nature, sometimes good people do bad things, but the vast majority of people are good or potentially good. We want to connect, to be polite, to engage, to feel something.

And as robots keep getting better at mimicking human interactions, many people will react to that. Why? Because we, as a society, are failing to provide real human connection. If people are forming emotional or even romantic connections with AI, we have to blame the weakness of our communities. People are thirsty for emotions, for connection, for conversation, for understanding, for politeness. They are thirsty for someone to be kind to them, for someone to help them altruistically, with no hidden agenda. And since they cannot find that with humans – where are they going to find it? With the robots that will keep mimicking humans – not being human but always mimicking. And for some people this might be enough… at least for a period of time.

- In the end of the same interview you said that with neuroscience we are able to “bring us down from some theoretical mountain of importance” to see what is really important. And I want to ask you – have you come to an answer to that question – what is truly important?

- The answer to that question has already been stated: it is human relationships.

There is an 86-year continuing longitudinal study at Harvard Medical School called “The Grant Study”. It began in the 1930s when they started following around 250 men later also included women and their children. Every year, they underwent medical and psychological tests. The researchers found that the level of healthiness and happiness of those people depended on the quality and quantity of human relationships. Those who had love, care, support, and friends lived longer and were happier – even slightly more successful.

So, if you want to know what your life will be like at your 80s, instead of looking at your blood pressure or your lab results at your 50s, look on what relationships you have.

When I ask people what makes us human, many say – thinking. But that is the theoretical mountain of arrogance and self-importance. Thinking does not exist for its own sake. Thinking exists for something. And what we now understand is that thinking evolved to help us interact better with others.

Thinking developed to help us navigate complex social interactions. The fact that we now use the same cognitive tools to write algorithms is wonderful, but it was not the original purpose.

So the answer, in the end, is: Humans. Always was. Always will be.

Gaiane Yenokian talked to Dr. Nikolaos Dimitriadis