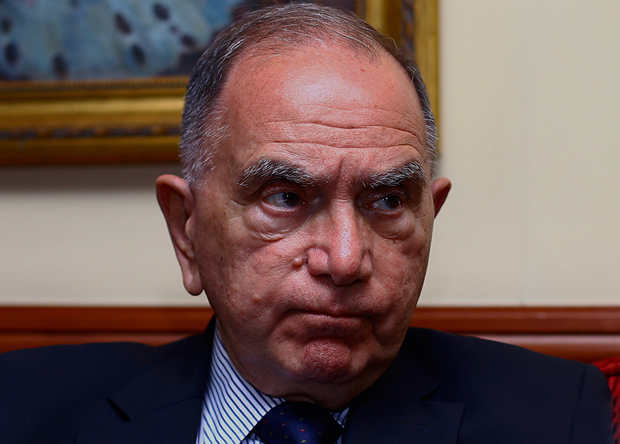

Edward Djerejian is the Director of the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University.

He is one of the country’s most distinguished and experienced diplomats – he has worked with the administration of 8 presidents of the United States. Edward Djerejian

played key roles in the Arab-Israeli peace process and regional conflict resolution. He is the author of “Danger and Opportunity: An American Ambassador's Journey Through the Middle East.”

Edward Djerejian managed to build up good personal relations with Syrian President Hafez al-Assad. There’s evidence that Syrian President didn’t hide that Armenian roots of the U.S. Ambassador played a significant role in it.

In 1985 Ambassador Djerejian was assigned to the White House as Special Assistant to the President and Deputy Press Secretary for Foreign Affairs. In 1981-1984 Djerejian was the Deputy Chief of the U.S. mission to the Kingdom of Jordan. In 1988-1991 he was the U.S. Ambassador to the Syrian Arab Republic. In 1991-1993 Djerejian was the Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs. In 1993 he was nominated by President Clinton as United States Ambassador to Israel.

Ambassador Djerejian is also an expert in Soviet and Russian affairs. He was assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow from 1979 to 1981.

According to some information, the U.S. decided to appoint Djerejian an Ambassador to USSR in 1990, but Moscow didn’t give agreement, fearing that an American Ambassador with Armenian name could cause problems in the situation of the expanding Karabakh movement.

At the request of Secretary of State Colin Powell, Djerejian chaired the congressionally mandated bipartisan Advisory Group on Public Diplomacy in the Arab and Muslim World. He also served as senior advisor to the Iraq Study Group (ISG), a bipartisan panel mandated by Congress to assess the situation in Iraq.

Edward Djerejian visited Armenia last week, where he held meetings with Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan, Catholicos of All Armenians Karekin II and Armenian Foreign Minister Edward Nalbandian.

Edward Djerejian gave an exclusive interview to Mediamax before leaving Yerevan.

- My first question is about the Aurora Prize Ceremony, which was the occasion for your visit to Yerevan. One of the co-founders of that initiative, Ruben Vardanyan, says that one of his ideas is to change the mentality of Armenian people. Do you think this initiative can bring changes to the psychology of Armenians living in Armenia and Diaspora?

- I believe it can. Certainly, the events themselves were outstanding, even spectacular in terms that it brought together so many people from different parts of the world. The most important thing is this basic model that Ruben and his colleagues put together, which is fundamentally to go beyond being a victim of the Genocide, which should always be remembered, because as came out in the Aurora events, genocide continues during our times.

You cannot deny the past. When you deny it, you’re just helping it to be repeated in the future. That has been a major message, but getting beyond that, keeping the remembrance valid but then building on that to see how the victims of genocide move forward in life not only as individuals but as societies and countries is one of the big lessons that the Aurora Prize represents.

I believe it’s a cultural change, it’s not only political, economic or social. It’s a real cultural change in attitudes and perspectives, which I think is very important.

I would call the Aurora Prize model a cultural movement that certainly will enhance Armenian people. Even the idea of granting a prize to non-Armenians who have helped the victims of genocide throughout the world shows that the Armenians are going beyond their own tragic experience and recognizing the others in the world. This is cultural change, and I think this will take Armenian mentality out of just focusing on the past to focusing on the future.

- You came to Armenia during a quite tense period after the four-day war. Do you see any possibility of return to negotiations or the time for that has gone and bad things are ahead?

- The time is never gone for negotiations, but right now negotiations would be extremely difficult, because these unfortunate and tragic military actions have set back the process. Emotions are high on both sides, and people are certainly loosing trust.

I think this is very dangerous because in the end of the day I do not think there is a military solution for the problem of Nagorno-Karabakh. The moral, political question comes - how many more people have to die or be wounded before the parties get to negotiation table?

The [OSCE] Minsk process has become too much of a process and not a real negotiation. That has to change, and I hope that in these recent clashes, this will sensitize not only Azerbaijan and Armenia, but Turkey, Russia and the whole international community, including the United States and France, that we have to get the parties to the table.

But the outside world cannot force a solution on the parties. The parties have to come to agreement on their own. The people of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Azeris, the Armenians have to come to that agreement. But the international community plays a very critical role, and right now the tension is so high you could feel it.

Edward Djeredjian

Edward Djeredjian Photo: Mediamax

I hope the leaders on all sides will act with wisdom and not play in to passion and emotion, and think of the long-term survival and prosperity of their peoples. At the same time I hope that the international community will realize that this so-called frozen conflict of Nagorno-Karabakh is not frozen. It will melt down and blow up in everyone’s face at the most unsuspected moment, as we just saw.

The international community and the parties of this conflict have to move from conflict management to conflict resolution. Conflict management is that you put out fires as they burst up, you get a ceasefire and bring at least a temporary peace to the parties. Nagorno-Karabakh, the Azeris, the Armenians, the Turks and Russians, the Minsk Group which is France, U.S. and Russia, and the international community in large must now cease upon this very fragile situation and work on getting the parties to the negotiation table and taking a hard look at what the contours of the settlement are, and try to activate realistic negotiations now that can get us to that point.

- You mentioned contours of the agreement. One of the key elements is the referendum or popular vote of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh. Do you think that Azerbaijan can ever accept the idea that people of Nagorno-Karabakh decide their own fate?

- I cannot speak about the intentions of the Azeris, but there are two major principles involved in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: self-determination of peoples and territorial integrity. Both of those issues are at the table. Armenians successfully occupied 7 districts around Nagorno-Karabakh and it puts them in quite a good negotiating position - they have something that the other side really wants, and it can be used in negotiations. You give up that, but in exchange you have to talk about the self-determination of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh and how you get there.

If Azeris are going to be responsible, they should recognize this international principles and come to the table. That’s what responsible countries do.

The fact is that it’s coming to the political will of the two countries, especially the leaders. At the end of the day, a lot depends on the leaders, their political will to negotiate a settlement and political courage, and third importantly to bring their people around to what the settlement would look like.

As I know from my experience as an American diplomat negotiating Arab-Israeli conflict, for example, if the negotiators’ positions are too far out from where the people are and the public opinion is, it just makes coming to a settlement more difficult, because you don’t have that popular support.

There’s Track Two diplomacy that I would suggest to the parties and the international community: honestly educate the peoples of Armenia and Azerbaijan that here what the issues are, here what the solutions are, and build up that support while you are negotiating. That’s very important. When we failed to do that in the Arab-Israeli context, we found it very difficult to come to a settlement.

- You mentioned Russia and Turkey. Do you think that tension in Russian-Turkish relations has somehow influenced this recent deterioration of situation in Nagorno-Karabakh or this is just a speculation?

- The international context around Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is very unfortunate today. Turkey has many problems that it’s dealing with, including the Syrian refugee crisis, the PKK, internal domestic politics. Turkey is not in the same position it was 10 years ago, perhaps, where it could look with a more beneficial view on the Nagorno-Karabakh issue.

Also, let’s be honest, Azerbaijan is always pressuring Turkey not to give in, in any way, to Armenia on the Nagorno-Karabakh issue. That makes the Turkish position complex, but Turkey is a very important country, it plays a major role in whatever’s going to be decided in Caucasus, especially Nagorno-Karabakh, so Turkey has to be called upon to play its role, and I hope it will be a responsible role.

Edward Djeredjian

Edward DjeredjianPhoto: Mediamax

Azerbaijan has to play a responsible role. The price of oil has gone down, Azeri financial position is not as strong as it was before, but it certainly was strong enough for all those years with the high price of oil and gas that the Azeri military were able to buy many weapons, systems that are now being used against Armenia.

The Russian position is very important in this part of the world. I’d say that probably Russia has the most powerful voice today in the South Caucasus. It has a military base in Armenia, it sells weapons to Armenia, but it also sells weapons to Azerbaijan. Russia is playing on the both sides of the fence. Having said that, if it wants to play a responsible role, it could take a very active part individually or in the Minsk context to bring the parties to negotiation table, and I hope it would be in the Minsk context.

I don’t think it’s in Russia’s interest for there to be a war in the South Caucasus. Putin is a smart player. I just don’t think that it’s in Putin’s or Russia’s interest to see chaos and conflict in South Caucasus, because that could lead to a further radicalization in the region. I don’t see how Russia would benefit strategically from another war in the Caucasus.

As for the United States, I know that Secretary Kerry is involved. By the way, as we’re speaking now today [April 26-Mediamax] Secretary Kerry is giving an important speech at my institute, the Baker institute in Houston, on the role of religion in foreign policy.

I know that he’s been in communication with President Sargsyan and President Aliyev, and the United States is taking a very close look at this very fragile situation. I know that Kerry is speaking with Lavrov, so there is attention being given. As I said earlier, what’s important now is that the Nagorno-Karabakh issue has gotten attention.

Four years ago I gave a talk to a large Armenian group is Pasadena. I usually don’t give these speeches, but I was urged by relatives of my father. I didn’t know what I was getting into, because when I got to Pasadena, I noticed, as we were driving to the sight of the event, hundreds of cars parked there. I got our of the car and I was immediately surrounded by four Armenian bodyguards. They had these little earphones in their ears, and I said “Oh my God, what’s this all about? I haven’t had bodyguards since I was U.S. Ambassador in Syria, what’s going on?”

The audience was huge, thousand people. I think some of the sponsors probably knew the contours of what I was going to say, they knew there would be Armenian groups in the audience that wouldn’t be happy with what I had to say. So I gave this speech, it was 2011-2012.

The basic thing is that I’m an advocate of Turkish-Armenian reconciliation, because I think it’s only when the state of Armenia that represents the Armenian people and the state of Turkey that represents the Turkish people sit down at the negotiating table and begin to negotiate on the critical issues that separate Armenia and Turkey, will there be real stability in the region and for Armenia.

I also said that the Genocide issue is not an issue that’s going to be resolved by the Armenian Diaspora. It will be resolved between the state of Armenia and the state of Turkey. It’s in that context that with an improvement of relations between Turkey and Armenia, I am very confident that as years go by the Genocide will be recognized by Turkey, but it will have to be in the context of normalization of the relations between the two countries.

Edward Djeredjian

Edward DjeredjianPhoto: Mediamax

Then I went further (laughs-Mediamax) and I said on Nagorno-Karabakh that Armenia is in advantageous negotiating position because it won the war and is occupying these Azeri districts. It has a huge bargaining chip in this equation of land, peace, self-determination of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh. Use it before it’s too late. Azerbaijan is going to make a lot of money out of its oil and gas. It’s going to be able to afford the beef up of its military, defense forces, and at the next war, the Armenians may be at a distinctive disadvantage.

Now is the moment. Some people thought that I was being alarmist, but I was being realistic. We face the situation today. It’s not that we don’t know what the issues are, that we had to foresee these things would have happened. It’s that we haven’t been able collectively, internationally, in Armenia and in Azerbaijan to have the political will to make this negotiating process go forward.

The art of diplomacy is really creating a political landscape where it becomes very difficult for the opposing parties to say no to one another. We did this at Madrid Peace Conference, when I was U.S. Ambassador to Damascus and Hafez al-Assad was the Syrian President. He didn’t want to sit at the table and direct negotiations with Israel. He wanted the UN as a buffer, because he felt that Israel was much more powerful than the Arab countries and that without a UN referee the Arabs would be disadvantaged at the negotiating table. Under President Bush and Secretary Baker and people like me in the field, my ambassadorial colleagues, we were able to help get al-Assad to decide to direct negotiations with Israel. It was a big breakthrough. The we got the PLO on board, we got Israel, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, we got everyone on board. It took a lot of negotiations. Some people say we pressured everyone, but what we did was we said “Here’s an alternative scenario. You sit down, you have guarantees from the United States of America on the negotiating process. Upfront you know that you’re not going to lose what you think is vital to your interests.” Secretary Baker gave Letters of Assurance to the Israelis, the Syrians, the Jordanians, the Palestinians, etc.

Edward Djeredjian at his office

Edward Djeredjian at his officePhoto: Edgar Barseghyan/100LIVES

I give you that example because I think something similar is here in Nagorno-Karabakh. The parties now, if you look at it, are really at polar opposites and nobody wants to sit down and negotiate right now. Eventually, they’re going to have to. The sooner, the better. It’s probably going to be some cooling off period now, but that cooling off period should not be allowed to remain too long and the negotiating process should be put in place. The diplomacy should first understand the positions of the parties fully and then see what common ground may exist between the two, and then start negotiations on the basis.

The contours of the settlement are well-known. There’ll be some changes and some modifications, but basically, as I said, territorial integrity for the Azeris and self-determination for Nagorno-Karabakh, the Lachin corridor, phased withdrawal of Armenian troops from some of these districts for international guarantees.

Armenians have a realistic question, which is “How about if we give up all this territory and the Azeris agree for a moment and then turn their backs and say they changed their mind?” That’s when you have international guarantees, a multinational force that’s satisfactory to both sides, and you have confidence building measures put in place. It can be done.

- After the last war, there was a lot of public comments and articles comparing Armenia and Israel. Many people suggest that Armenia should follow Israel’s example in building a very well-organized state where the army isn’t only a guarantor of people's security, but a driving force for technology, business, etc. Given your experience in the Middle East, do you see Armenia taking example from Israel in some ways or it’s totally different?

- It’s an interesting question. I think there are some parallels, although not exact. For example, Israel considers itself to be a Jewish state, Armenia is a Christian state. You know the glorious Christian history of Armenia. I just came from Etchmiadzin, I was meeting Vehapar (His Holiness).

It’s very difficult to differentiate between the Armenian state and the Armenian Church, it’s a very special relationship. It’s the same thing in Israel, the Jewish religion and the state of Israel. There’s a commonality there. Second, Israel didn’t have many natural resources, Armenia doesn’t have that many natural resources, but both countries have an incredibly intelligent population, smart people on both sides. They’re creative, and they’re entrepreneurs, certainly you can say that for the Jews and the Armenians.

Therefore, I think those common points can make of Armenia a very vibrant crossroads in the Caucasus region and beyond, a North-South-East-West crossroads. You already have a very good high-tech and IT sector. You could build that way beyond what it is now, and that’s really the genius of the Armenian people at play there. You could become a centre for commerce between East and West, North and South. The possibilities are great. Armenian culture, the music, the art - it could really become something rather extraordinary like Israel has become. You do all this without the so-called curse of oil and natural gas, because as we’ve seen having oil and gas in your country is a very good thing financially and economically, but it also can be a curse.

Edward Djeredjian at his office

Edward Djeredjian at his officePhoto: Edgar Barseghyan/100LIVES

But what Armenia also has to do, and Azerbaijan certainly has to do this too, is it must work at making the Armenian society and government more transparent and root out corruption. I understand that some real progress has been made in rooting out retail corruption, but corruption in a society will impede that country from making the best decision for the people and the nation, and that certainly applies to Azerbaijan, where there is systemic corruption. That’s a long-term evolution, but that change has to come from within, in both countries.

That’s why I think that when new ideas like we witnessed at the Aurora Prize, where you change the model to one where you try to unleash all the social, cultural, economic, innovative, entrepreneurship talents of a people, is a movement. I think that’s what we’re beginning to see. I think that will be very beneficial to the Armenian people. When you talk about the Genocide, the worst thing that could happen to the Armenian people is that having survived the Genocide we do not move forward as a people in peace and prosperity and have a strong Armenian state, with which we’ll represent the victory of Armenians over death.

- You mentioned parallels between Armenia and Israel, but unfortunately, the interstate relations aren’t so good. Do you think there is a chance to improve the relations or issues like Armenia’s relations with Iran and Israel’s ties with Turkey are hindering?

- I’m going to be in Israel about a month from now, at a conference. I’ll be able to answer you questions better then (laughs). I think the Israelis have just made a very political calculus that Azerbaijan can be a partner with Israel vis-à-vis Iran, because they consider Iran to be a very important threat, and establishing relations with a country like Azerbaijan which is on the borders of Iran gives Israel another point of influence in their future dealings with Iran. I think that’s the main reason.

There’s also many business interests involved, unfortunately. People are making money, Azeris have a lot of money and so contract are being made in the military field also, which is very troubling. They’re selling very sophisticated military technology to the Azeris. It’s unfortunate in my eyes, because the Israelis have been the victim of genocide, the Armenians have been the victim of genocide, and the similarities that are expressed should mean something, because they’re based on values. And Israel likes to consider itself a value-based society.

- Back in 1999, you and you colleague Peter Rosenblatt came to the region to discuss some ideas on Nagorno-Karabakh. Can you disclose some of the ideas?

- Yes, it’s not a secret anymore. We did the shuttle diplomacy between Baku and Yerevan, and I think the Azeris were very surprised to see me come (laughs). I came with my son, and they were so surprised. We did this shuttle diplomacy by just laying out to the Azeris and the Armenians what the common points of negotiation could be. We went back and forth and we saw that there was a real prospect, there was some hope of reconciliation, but also saw the difficulties.

The contours were basically what we talked about. We tried to promote some good will gestures. We got very little, unfortunately, especially at the side of the Azeris, but we made the attempt. I didn’t engage again because I saw the situation was frozen and we couldn’t really make an important difference. I hate doing things just for the sake of doing them, but if an opportunity comes up we can do something important.

I believe that you enter into a strategic dialogue with your enemies in order to make peace. You don’t have to enter into a strategic dialogue with your friends as necessarily as with your enemies. That’s why I support President Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran, because I think it’s the best alternative that we had, and I think they successfully negotiated that. And the opening to Cuba. I have some problems with the administration’s Middle East policy, especially vis-à-vis Syria, but other than that, I think what they did in Iran and Cuba can be a guiding post - you can overcome your differences. The Armenians and the Azeris has to see that. The people of Nagorno-Karabakh should obtain their legitimate self-determination. Everyone’s going to have to compromise. Compromise is part of life and diplomacy.

Ara Tadevosyan talked to Edward Edward Djerejian